Yasmeen Shorish is Associate Professor and Data Services Coordinator at James Madison University. Yasmeen is the Chair of the ACRL Research and Scholarly Environment Committee, Co-Founder of the Digital Library Federation Technologies of Surveillance Group, and Co-PI of the IMLS funded Supporting OA collections in the open: community requirements and principles. Yasmeen holds an M.S. in Library and Information Science, a B.S. in Biology, and a B.F.A. in Theatre from the University of Illinois.

Thomas: Thank you for the taking the time for this conversation. You are engaged in efforts that span scholarly communication, data information literacy, and representation and social justice in librarianship. Over the course of this conversation we’ll touch upon each, but before digging in can you talk a bit about what led you to where you are now?

Yasmeen: I had a very circuitous path getting to where I am now so it’s difficult to capture succinctly. I have a BFA in technical theater and I worked in the entertainment industry in Chicago before transitioning to librarianship. That experience influenced a lot of how I approach the profession. For example, I’m very outcome-oriented and I look for collaborators with expertise in different areas. From my time in the entertainment industry I learned that diversifying expertise often creates a stronger process and product.

I have been an advocate for representation for as long as I can remember. I was part of the University of Illinois Asian American Artists Collective and contributor to its publication Monsoon while I was still in high school! After 9/11 I did some public speaking in Chicago for Afghan women’s rights but it was hard to do that work and my day job. I realized that I needed my career to be something that connected with my core beliefs and made a positive contribution to society. By that time, I had completed a second bachelor’s degree in biology while working full-time. Struggling with next steps my advisor suggested librarianship. Once I learned more about the profession I realized that it was the best path for me. I didn’t realize at the time how monocultural librarianship is but nonetheless it is refreshing to have the opportunity to advocate for representation and social justice as part of my work.

Thomas: Last year, you and Shea Swauger kickstarted the Digital Library Federation Technologies of Surveillance group. Can you speak a bit about why the group started? Have the goals changed or remained the same?

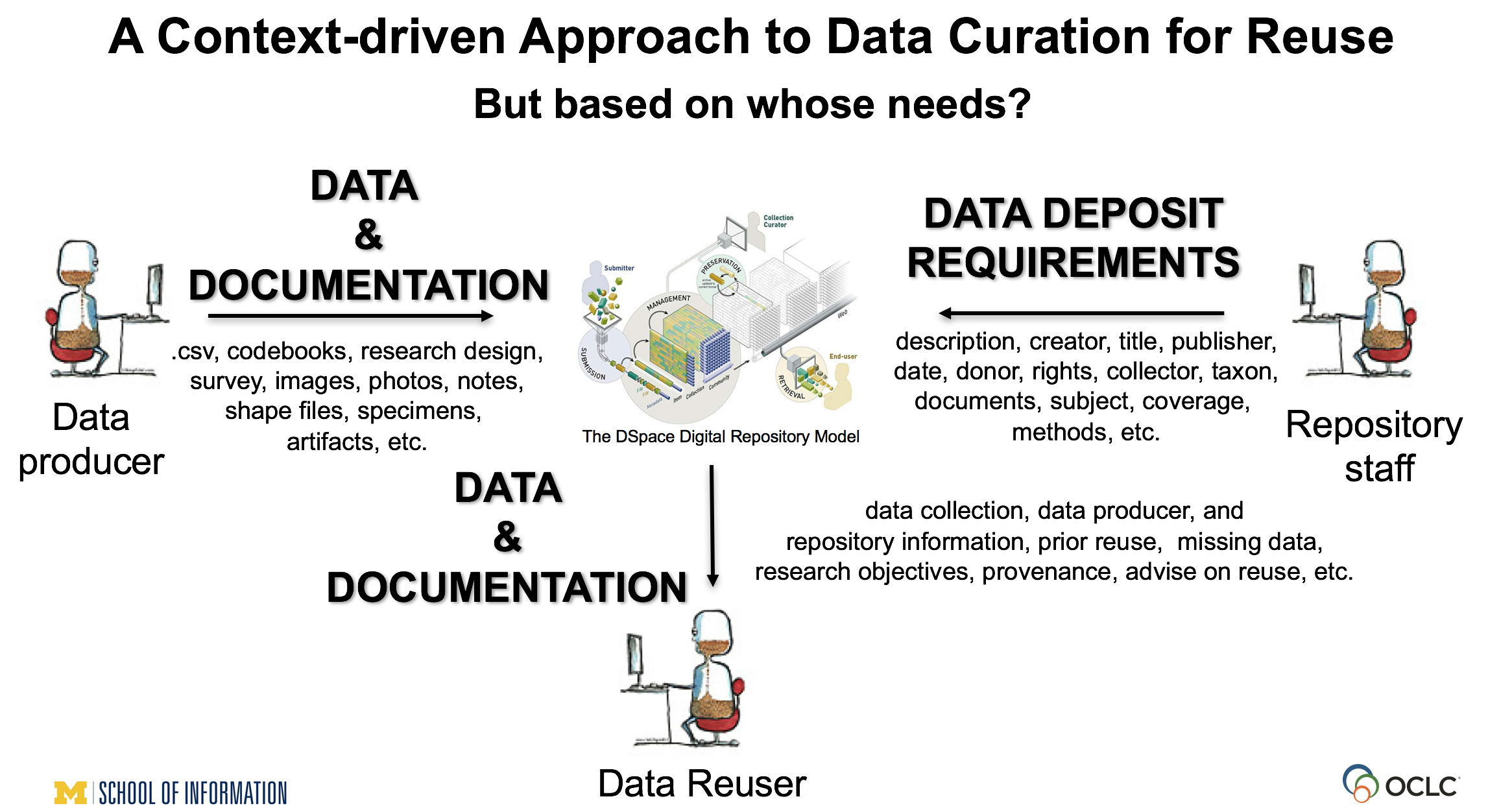

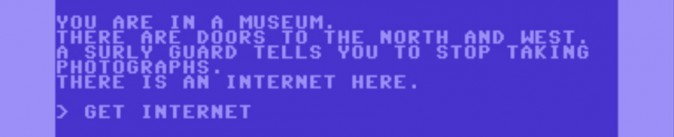

Yasmeen: For some time I had been really concerned with the proliferation of surveillance technology in our everyday lives. The market dominance of products like Alexa and other Internet of Things (IoT) innovations make me really anxious. In librarianship we have a real need for conversations and practices that help us meet the challenges that these technologies pose. Fundamental library work positions us to be advocates in this space. For example, the “information has value” frame of information literacy and our work with metadata and systems provide a good foundation.

At RDAP 2017, I found that Shea and I shared some of the same concerns. At DLF 2017 we presented Surveyance or Surveillance?: Data ethics in library technologies. I asked Bethany Nowviskie if she had ideas for how we could increase engagement with the topic moving forward and she encouraged us to think about forming a working group. She also provided inspiration for the working group name which she had coined in a few of her writings.

The goals of the working group, at the core, remain the same: to interrogate data collection technologies, to document their ethical implications, and to establish guidelines that support critical engagement throughout the profession.

As I mentioned, I am outcome-oriented, so it is important to me that the group produces something for the community to use. Our areas of focus have expanded based on community input and I think we have been able to bring things together in a complementary way. Thanks to the leadership of Dorothea Salo, the group has already produced a document – Ethics in Research Use of Library Patron Data: Glossary and Explainer. We hope it will be taken up and used by the community. The working group is striving to have a more comprehensive document that encompasses the work of the various subgroups completed by DLF 2019.

So many people and projects inspire this work. Dorothea Salo, Bethany, Alison Macrina, Melissa Morrone … honestly I can’t name everyone because it would take up pages. Projects and groups like Data & Society, EFF, the Library Freedom Project, the IMLS Data Doubles project … there are so many allied initiatives that inspire the working group.

Thomas: Two things struck me from your comments above – the reference to ethics and your own disposition toward outcomes. It has been my sense that in a number of library communities we are becoming better at recognizing the ethical implications of our work – especially as they intersect with the broader realities of a de facto data driven culture. In terms of gaps, I’d like to see more discussion of ethics paired with development of corresponding actions germane to community need. As you work toward outcomes is there a particular form you would like them to take? Are there any models you look to that support making ethics actionable?

Yasmeen: This is complex. When I think about outcomes, I think of them as practical actions that can be taken up and implemented by a variety of practitioners. This requires that I think beyond the act of resource creation, i.e. “we made a document.” I work to anticipate how a resource will be used by diverse communities. I try to determine if the requirements for implementation are problematic – potentially not achievable in the reality of a different environment.

I don’t have a different style for “ethics work” compared to all my work. I just employ different calculations. These calculations lead to a lot of internal struggle as I try to thread the needle of optimal outcome in a sub-optimal environment.

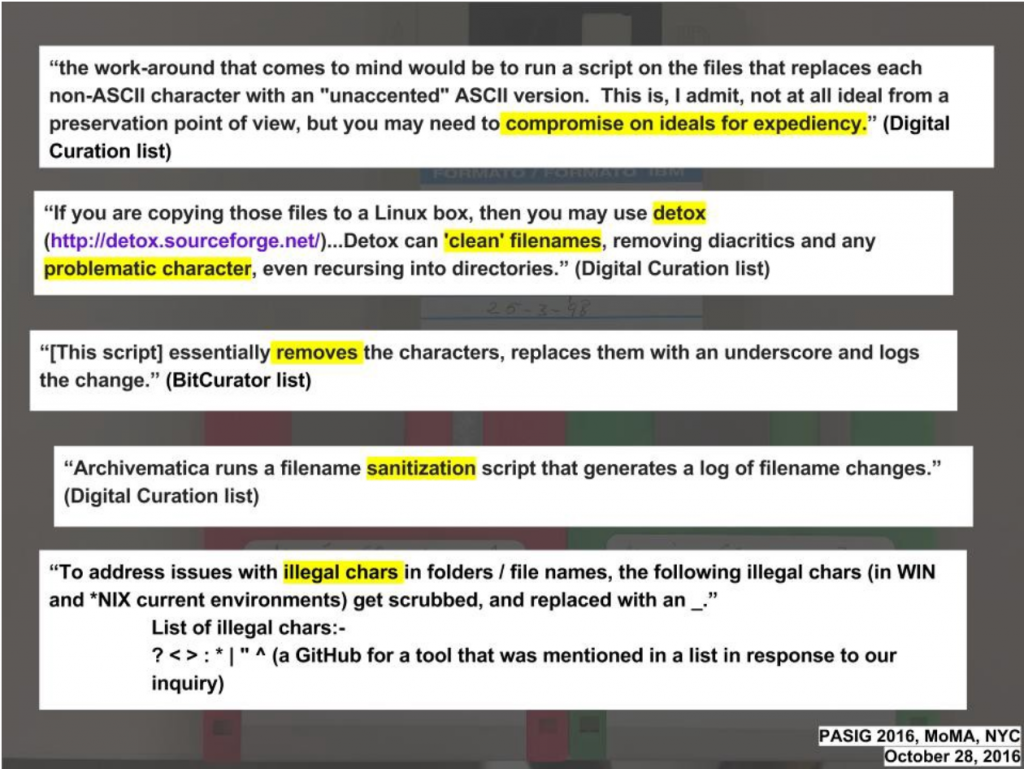

Sometimes ideal products must be diluted in order for them to be adopted, implemented, and embraced by a community. Again, I have a lot of internal struggle about this. I want us to take ethically-grounded actions – the most just actions – and trust that they will be championed and radical change will occur. I want us to do that, but I don’t think enough people in positions of power are willing to champion radical change and motivate buy-in from their communities.

I have no formal training in social sciences, behavior studies, or even the humanities. My background is in fine art and biology. The models I use to make ethics actionable are primarily informed by lived experience.

The first is the “take me as I am” model. This is the most uncompromising and idealized model – “Here are the most just actions required for the most just outcomes”. Often, the prevailing reality – for any institution or society – is not built with justice centered in the system so actions associated with this model often require radical change. The latter model requires more compromise and trust. The actions take longer to implement and the outcomes are potentially weaker. Compromise is made in order to foster change and engender less defensiveness from those who hold power. I personally feel conflicted about this model. This approach is often exhausting and is sharply felt by most any person of color working to effect change in white spaces. Dealing with white fragility is a constant.

Thomas: You serve as the Chair of ACRL’s Research and Scholarly Environment Committee (ReSEC). In consultation with ReSEC, Rebecca Kenison and Nancy Maron are working with a number of communities to develop the ACRL Research Agenda for Scholarly Communications and the Research Environment. I am encouraged by the focus on openness, inclusion, and equity – I am doubly encouraged by what appears to be a fairly robust discussion around what those terms could mean in the context of scholarly communication. In context, what do these terms mean to you? What sort of research would you like to see within this frame? Who could benefit from it?

Yasmeen: In the context of scholarly communication I think “open,” “inclusive,” and “equitable” should mean that we participate in systems where myriad ways of knowing are valued, are accessible, and are supported.

In the United States, knowledge systems are guided by a “Western” or Euro-American culture. This isn’t inherently bad, but the systems are exclusive, such that “other” practices are viewed as invalid, trivial, or suspect. I recently read an article by Kirsten Broadfoot and Debashish Munshi that is hugely relevant. They argue that implementation of a postcolonial academic culture is challenging because Western epistemology has become so widely internalized – a hegemonic state. When I think of how we can make scholarly communication more just, I consider a number of dimensions: academic disciplines, publishing, the marketplace, systemic racism, sexism, entrenched socio-political structures … it’s a lot!

I’d like to see more research on representation of authors and creators across fields: who is contributing to the information landscape; what topics are under and over-represented; presence or lack of presence of publishing venues that are supportive of non-dominant epistemologies; the relationship between classification and “normative” experience; user privacy; the capacity for technical platforms to provide more just representations of knowledge. I’d like to see findings brought to bear on the library – the catalog, the institutional repository and so forth.

Honestly, the whole thing is overwhelming. I have a hard time writing about the enormity of the situation and all the opportunities that we have to contribute to positive change. A more just system doesn’t only benefit those of us who have been discouraged from participating or whose voices have been silenced. A more just system benefits humanity. Individuals or groups may lose positional or social power with some of these changes, but there will be more communication, more sharing, on more even footing.

These changes will not be without conflict and friction, but if we can move the needle towards a more collaborative and communicative society, shouldn’t we make the effort? Not as advocates from the margins, but as a body, representing the best aspects of our profession?

This is why I have a fair amount of hope attached to the ACRL efforts with the research agenda. ACRL represents its members and parts of the profession. If the Association can help provide the reasoning and the tools to help practitioners engage with these weighty and complex topics we may see more movement across the profession to do this difficult but meaningful work.

Thomas: Following on that, you are Co-PI for the IMLS funded Supporting OA Collections in the Open. What do you hope to achieve with this project? How can people interact with the project?

Together with co-PI, Liz Thompson, and our project partner Judy Ruttenberg at ARL, I hope that we can get at what the academic library community really requires to move towards authentic collective action on open access collection development. We’re currently conducting focus groups with participants from various types of institutions (e.g. liberal arts colleges, community colleges, HBCUs, research universities) and from various roles within the library (e.g. acquisitions librarians, scholarly communication librarians, library deans, e-resource librarians, subject librarians). We are bringing them together in a room to try to get at their priorities and needs. After we’ve synthesized the focus group data, we will produce a white paper of our findings with the hope that others in the community will build upon those findings and move the project forward. We will present our findings and hopefully have robust conversation about the project at the 2019 DLF Forum in October.

Thomas: Lastly, whose work would you like people to know more about?

Yasmeen: Seriously, way too many to name. This question is going to give me anxiety because I will think about all the names I want to add.

I have been incredibly lucky to know generous people, who have shared their knowledge and experiences with me. I have mentioned several already, but I would like to add Emily Drabinski for her work on labor/power and also her writing on the human condition; Bergis Jules, because even though our views sometimes differ, I appreciate and respect his perspectives on community-controlled cultural heritage so much; Mark Matienzo, because I appreciate the ways they think about technology and culture; Charlotte Roh, because she has such critical insights into publishing systems; Anasuya Sengupta and Siko Bouterse (both of Whose Knowledge?) because they are doing amazing work, across the globe; and, lastly, authors whom I do not know personally, but people should know more about: Rumi and Hafez, for writing about one’s spirit through a lens of connectivity and also humor (and I’m talking about the Masvani for Rumi – not the bite-sized phrases that are divorced from the work); Haruki Murakami, for his non-linear writing that is way better than Thomas Pynchon or William Burroughs (don’t @ me); and Art Spiegelman, for writing Maus – a highly accessible work that helped me explain war to others who have never had to consider it and because it reminds us of the things that humans are capable of.