Ixchel Faniel is a Research Scientist at OCLC Research. Faniel has conducted extensive research into how various disciplinary communities approach research data reuse. Faniel served as Principal Investigator on the Institute for Museum and Library Services funded DIPIR (Dissemination Information Packages for Information Reuse).

Thomas: Believe it or not, I think you may be the first Research Scientist I’ve corresponded with! Can you tell me a bit about your role at OCLC and what combination of experience, education, and interests led you to it?

Ixchel: I’m laughing because I didn’t set out to be a Research Scientist, but given my experience, education, and interests, I can see how I ended up at OCLC. My role is to conduct research that informs and impacts the communities OCLC serves in terms of what they do and how they do it – so libraries, archives, museums, their staff, and their patrons. Typically, my interests center on people and their needs. At a high level I’m interested in how people discover, access and use content and how technology supports those things. My interests grew out of my experiences and education for sure.

After graduating from Tufts University with a B.S. in Computer Science, I worked at Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) as a consultant, designing and developing information systems to meet clients’ needs. I spent a lot of time at USC earning my MBA and Ph.D. in Business Administration at The Marshall School of Business. The time between the two degrees was spent at IBM selling mainframes and working with a team to propose total solutions – hardware, software, services – to solve a customer’s specific business problem. Working as an Assistant Professor at the School of Information, University of Michigan also shaped my interests, because I was exposed to different conversations – federal funding agency mandates to share research data for reuse, data repositories, research collaboratories, team science, cyberinfrastructure.

Primarily, my interests have focused on the reuse of research data within academic communities. I’m particularly interested in the kinds of contextual information that need to be captured along with the data and how context can be curated and preserved. This line of work started with National Science Foundation funding when I studied how earthquake engineering researchers reused each other’s data. It continued with DIPIR (Dissemination Information Packages for Information Reuse), a multi-year Institute of Museum and Library Services funded project to study the data reuse practices of social scientists, zoologists, and archaeologists. Recently work in the area has been extended with National Endowment for the Humanities funding for the Beyond Management: Data Curation as Scholarship in Archaeology project. It’s a longitudinal study of archaeologists’ data creation, management, and reuse practices to investigate data quality and modeling requirements for reuse by the large community. A second line of related work I began at OCLC examines the role of academic libraries and librarians in supporting researchers’ data sharing, management, and reuse needs. It serves as a nice complement to studying the researchers, because librarians and libraries are viewed as a key stakeholder group. I’m currently examining their early experiences designing, developing, and delivering e-research support.

Thomas: I am intrigued by the link you drew between technology supported knowledge reuse for innovation and data reuse within academic communities. Can you speak to this in greater detail?

Ixchel: Sure. So when I was studying knowledge management and knowledge reuse within organizations, one of the major issues was that it was contextual in nature. In order for one colleague to understand another colleague’s knowledge well enough to apply it to a new situation, there was a need to know the context within which it was created. The difficulty was having access to all of those details in absence of the colleague. In going about doing work, employees were creating a paper trail for some things, but they weren’t necessarily capturing everything related to how and why they were doing what they were doing. In other cases, employees were capturing a summary of events in a final, formal document to be stored and shared as corporate memory, but keeping documents they generated in the course of creating the final document to themselves. Those additional documents served as a detailed reminder of how they arrived at the final document, but weren’t necessarily shared with others. In other cases, employees were relying on their past and present experiences and that knowledge they were using in the moment to make a decision, solve a problem, or develop a new product was tacit and not captured.

[pullquote]Similar to employees who generate knowledge, researchers who generate data may be recording some context but not necessarily all context, or they’re sharing some context but not necessarily all context.[/pullquote]These are some the same issues we face in studying reuse of research data within academic communities. Similar to employees who generate knowledge, researchers who generate data may be recording some context but not necessarily all context, or they’re sharing some context but not necessarily all context. They are doing this not to withhold information necessarily, but because they don’t think to record or share certain kinds of context. In some cases the context represents something they do so regularly in the course of their research that it becomes tacit or such a minor detail to them that they don’t think to include it. Researchers have not had to document data beyond personal needs before federal funding agency mandates to share data and write data management plans. Are they capturing enough about the context of data production such that others can come along and reuse that data to answer different research questions or make a new discovery? I wasn’t sure and I didn’t think we would really know until we started asking researchers who reused data what they needed.

Thomas: Nearly five years ago, you and Ann Zimmerman wrote, Beyond the Data Deluge: A Research Agenda for Large-Scale Data Sharing and Reuse. In that paper you outlined an ambitious research agenda for yourself and a wide field of scholars and practitioners. I imagine a fair amount of work has happened since then. Thinking on that work, where are we now?

Ixchel: Good question. Where are we now? Making lots of progress, but there is still more to do. Ann and I developed that research agenda around three activities we thought needed more attention – 1) broader participation in data sharing and reuse, 2) increases in the number and types of intermediaries, and 3) more digital products.

We’ve definitely seen more research examining data sharing and reuse. When we wrote the article, we were both in agreement that the research on reuse was sorely lacking and had both done early work in the area to examine data reuse practices among ecologists and earthquake engineering researchers. Interestingly our article was written around the same time Elizabeth Yakel and I were waiting to hear whether the DIPIR project was going to get funded.

Luckily it was funded. As I mentioned earlier, DIPIR is a study of data reuse practices of social scientists, archaeologists, and zoologists. We were particularly interested in what kinds of contextual information were important for reuse and how it could best be curated and preserved. Over the years we’ve published studies considering how social scientists and archaeologists develop trust in repositories, examining internal and external factors that influence archaeologist and zoologist attitudes and actions around preservation, studying the relationship between data quality attributes and data reuse satisfaction, and discussing the topology of change at disciplinary repositories.

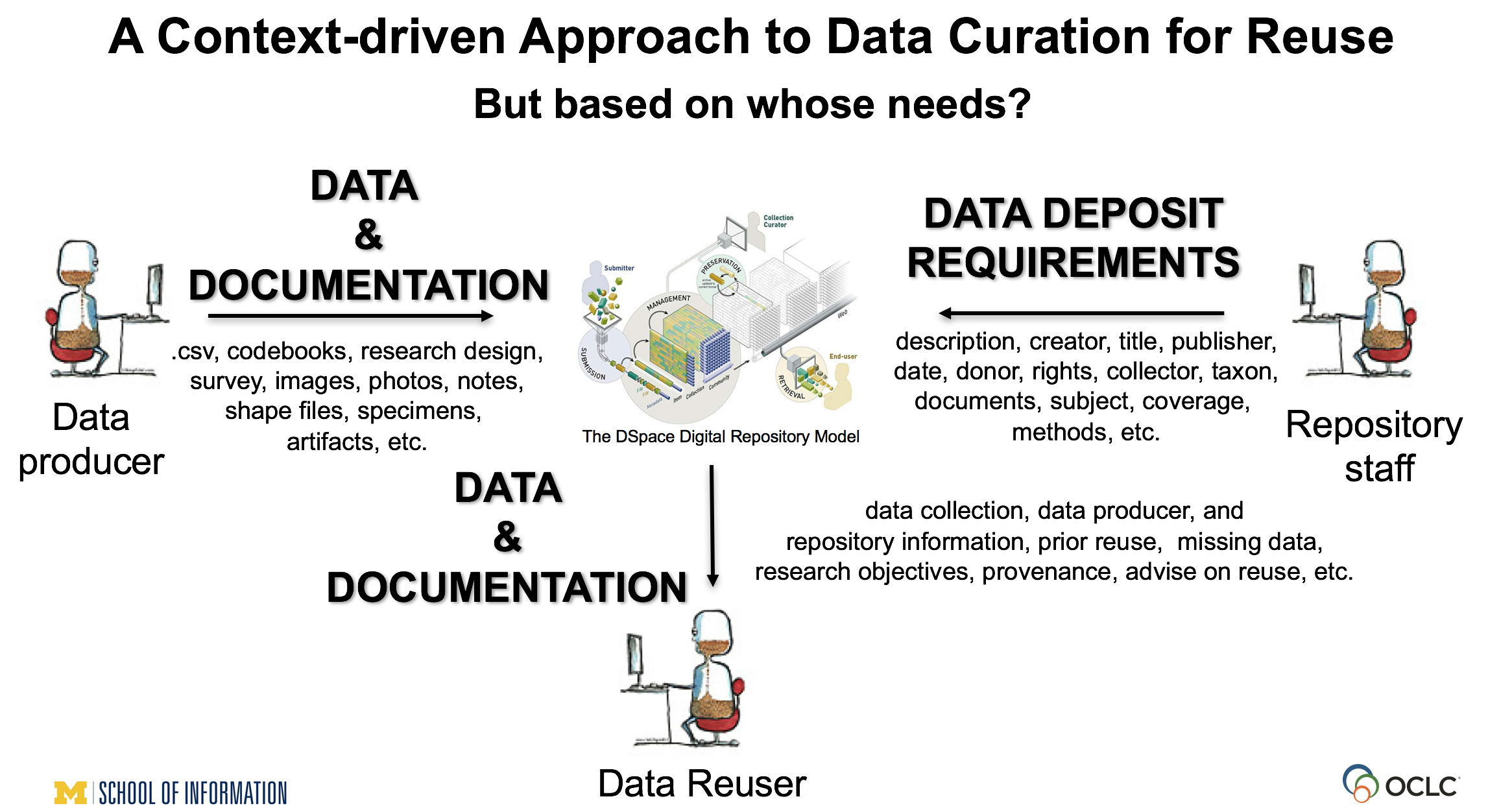

Most recently we’ve been doing a lot of work describing our context-driven approach to data curation for reuse we used for the DIPIR project. Initially, our major goal with this approach was to give voice to the reusers’ perspective, understanding that it influences and is influenced by the other stakeholders involved in the process. Now we are working toward providing a more balanced picture of needs among the major stakeholders (data producers, data reusers, and repository staff), knowing that they may have different, sometimes competing, data and documentation needs. We started narrowly by bringing reusers’ perspectives to the fore, but we’ve been slowly expanding to include these other stakeholders.

In February 2016, we convened a workshop at the International Digital Curation Conference to share our approach and findings. We collaborated with Kathleen Fear, Data Librarian, University of Rochester and Eric Kansa, Data Publisher, Open Context. Both also do research in the area, but their primary responsibility is supporting researchers’ data sharing, management, curation and reuse needs. They talked about the impact DIPIR findings were having on their practices, including the tradeoffs they had to make. To complement the presentation, we engaged workshop participants in card sort exercises to consider the importance of different types of contextual information given the needs of data reusers vs. repository staff. With the workshop one of our objectives was for participants to see the partnership or the marriage between research and practice as well as differences in needs not only among data reusers and repository staff, but also among data reusers within different disciplines and repository staff supporting different designated communities of users.

Thomas: Where do you think work of this kind is headed next?

Ixchel: I believe these kinds of connections – connections between researchers studying the phenomena and practitioners implementing it – are one thing that can help advance work in the area. And even among the researchers diverse experiences are important. Elizabeth and I came together given her background in users, archives, and preservation and my background in users of information systems and content. During our research we’ve engaged with different perspectives and literatures that have some similarities but haven’t always talked to or referenced one another. One of our goals was to bridge those areas.

[pullquote]My goal was to convince archivists to bring their expertise to the table in conjunction with an understanding of data reusers’ needs to inform not only the preservation of data’s meaning, but also other archival practices, particularly the partnerships they form.[/pullquote]Bridging is an important part of this effort. I wrote about a particular aspect of it in a two part blog post after participating in a panel on Data Management and Curation in 21st Century Archives at the Society of American Archivists Annual Meeting in 2015. My goal was to convince archivists to bring their expertise to the table in conjunction with an understanding of data reusers’ needs to inform not only the preservation of data’s meaning, but also other archival practices, particularly the partnerships they form.

A key part of my message was archivists cannot go it alone, because curation and management is bigger than the archive. My related study of librarians confirmed it; communication, coordination, and collaboration with other campus entities was particularly important when supporting research data services. Presentations from fellow panelists also confirmed it. What struck me about their presentations was whether and how they and their colleagues came to value each other’s complementarities in order to deliver more effective research data services.

It would be great to see more work about whether and how data and information researchers and professionals begin to partner with each other and other organizations. There has been some work to frame the issue from Brian Lavoie and Constance Malpas, colleagues at OCLC. They conceptualize evolving stewardship models. Seeing additional research in this area and how it’s done in practice, particularly within and across colleges and universities would be interesting.

So when Ann and I talked about increases in the number and types of intermediaries one of the areas we suggested examining was how education, roles, and responsibilities were changing given the evolving nature of data and information professionals. There has been nice progress in those areas from Liz Lyon at the University of Pittsburgh, Carole Palmer at University of Washington, and Helen Tibbo and Cal Lee at UNC Chapel Hill. Going forward it will be interesting to examine career trajectories, how do they advance in their professions, what is rewarded vs. not.

With regard to the last area Ann and I discussed – more digital data products or new types of digital products that include or reference data – The Evolving Scholarly Record presents a framework to organize and drive discussions about it. More recently, Alastair Dunning wrote a nice blog post while at the International Digital Curation Conference summarizing Barend Mons and Eric Kansa’s approach to publishing data and how it benefits reuse – Atomising data: Rethinking data use in the age of explicitome. But that’s just the beginning. There’s definitely room for more work in this area, particularly other approaches being taken in other disciplines given the needs of data producers, reusers, and repository staff.

Thomas: Whose data praxis would you like to learn more about?

Ixchel: That’s an interesting question. For me it’s the data producers and curators. So for the past several years I’ve been working with colleagues to get data reusers’ perspectives inserted into conversations, but by no means do I think it is enough. We’ve done some work examining Three Perspectives on Data Reuse: Producers, Curators, and Reusers, starting at the point of data sharing. It goes back to the context-driven approach. Data producers are the ones who are setting the tone regarding data management, curation, and reuse really, because they are upstream in the data cycle. The NEH funded project I discussed earlier – Beyond Management: Data Curation as Scholarship in Archaeology – aims to bridge data creation and reuse.

The project started in January 2016. We have this fantastic opportunity to interview and observe archaeologists while they are collecting and recording data in the field during archaeological excavations and surveys and interview archaeologists interested in reusing the data. The objective is to examine data creation practices in order to provide guidance about how to create higher quality data at the outset, with the hope that downstream data curation activities become easier, less time intensive, and data creation practices are better aligned with meaningful reuse. We have another great group of people working on the project specializing in archaeology, anthropology, data curation and publishing, information science, archives and preservation, etc. and we are all focused on studying data creation and reuse and impacting practice. I’m looking forward to seeing how it progresses. It should be a lot of fun.