Mia Ridge is a Digital Curator, working within the Digital Scholarship team at the British Library. Mia holds a PhD in Digital Humanities (Department of History, Open University). She has published and presented widely on user experience design, human-computer interaction, open cultural data, audience engagement and participation in the cultural heritage sector, and digital history. Her edited volume, ‘Crowdsourcing our Cultural Heritage’ was published in October 2014.

Thomas: Your dissertation and much recent work has focused on crowdsourcing and other forms of cultural heritage collection engagement. What came before? What experiences prepared you for this particular area of focus?

Mia: A little while ago I found a forum post from the late 90s where I enthused about the power of the internet to democratise knowledge, so I guess some of my views stem from that optimistic pre-first dotcom boom moment when the web seemed more focused on information and discussion than on e-commerce. Not too long after that, I started working with the Outreach team at Melbourne Museum / Museum Victoria, where the web was seen as just one potential form of outreach, one of many ways to connect people with historical, cultural, and scientific collections.

[pullquote]I’d noticed that people needed some kind of prompt to stop and look at collections – simply putting them online isn’t enough.[/pullquote]My work on crowdsourcing in cultural heritage connects that focus on shared knowledge and collections with the challenge of designing projects that provide enjoyable activities that in some way contribute to a greater good. Working in British museums gave me a sense of the size of collections and the vast amount of work required to document and make them discoverable online compared to the resources available to do that work. At the same time, I’d noticed that people needed some kind of prompt to stop and look at collections – simply putting them online isn’t enough. I have always believed that cultural heritage organisations should find ways to engage everyone with our shared histories and cultures, which sometimes means thinking creatively about reducing barriers to participation and access.

In the spirit of Luis von Ahn and Laura Dabbish‘s games for social good and building on projects like steve.museum, my 2011 masters dissertation for my MSc in Human-Computer Interaction explored crowdsourcing games for museums. The games I made were designed to encourage people to create metadata while playing with ‘difficult’ (i.e. less visually accessible) museum objects, particularly objects from history of science and social history collections. I found that the games gave people an excuse to spend time looking at collections they’d otherwise walk past, and that the act of looking at something long enough to describe it with keywords created a sense of engagement with that object. I hadn’t expected to find that relationship between crowdsourcing and engagement, but it’s informed my work since then.

Thomas: At Digital Humanities 2015 I had the distinct sense that many folks were griping (in a good natured way) about all the distance they traveled to get to Australia. Of course some of the Australians in the group reminded the rest that this sort of travel is par for the course for much of their engagement with the international community. I’ve noticed for awhile now the wealth of unique, digital cultural heritage collection activity happening in Australia. Tim Sherratt, Deb Verhoeven, Fiona Tweedie, Sebastian Chan, and Mitchell Whitelaw come to mind. As an Australian, do you think there is something about distance or about the Australian cultural heritage community in particular that encourages some of the neat work we’ve been seeing? Is there any work in particular that is emblematic of that environment in your mind?

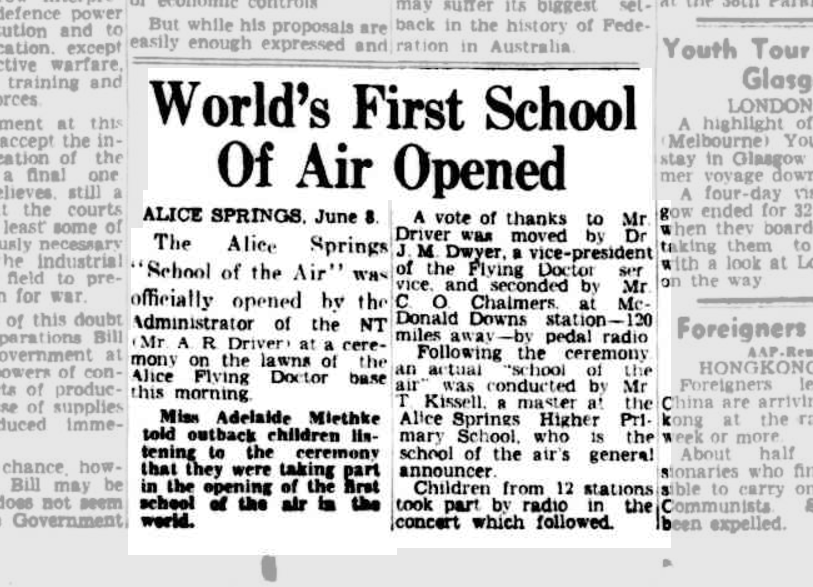

Mia: I think there is something about distance that affects our attitudes to overcoming obstacles. Australia is a sparsely populated country, and pre-digital organisations like the School of the Air and the Flying Doctors were well-known models for delivering services over vast distances. When I started working in the cultural sector in the late 1990s, people were still driving vans across the country to deliver training programmes to get people online or to take museum objects to sessions in rural schools and nursing homes. Working online was a continuation of those outreach programmes. Being an expensive and long flight away from things only available in Europe, Asia or the Americas – whether artworks, historical sites, theatre, festivals or gigs – might also mean that ordinary Australians intrinsically get the value of online experiences or information.

Perhaps there’s something about dealing with distance and the clear need for services for remote communities that focused minds on collaborative, productive approaches to making cultural heritage available online. I’ve always wondered how much portal projects like Australian Museums and Galleries Online (AMOL; see for example this 2002 description of what later became the Collections Australia Network), the National Library of Australia’s Trove, and the Canadian Heritage Information Network’s (CHIN) Virtual Museum of Canada, launched in 2001, were a response to distance. Large countries with slightly smaller populations, like New Zealand or Finland, have produced even more comprehensive infrastructures (DigitalNZ and CultureSampo respectively) for sharing their heritage online.

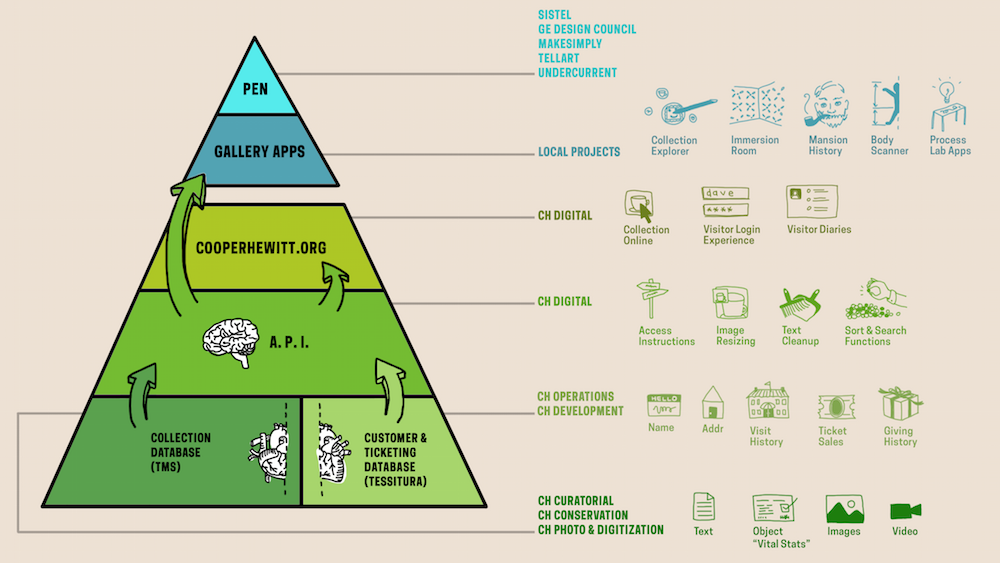

Thomas: You’ve worked extensively in the museum community, particularly with projects and initiatives around the idea of “open cultural data.” For our library audience, can you describe open cultural data as it’s talked about in the museum community? What are some of the key challenges and opportunities afforded by this frame of thinking?

Mia: That’s a doozy of a question! Answering it means thinking about the differences between museums and libraries (and the differences between research libraries and lending libraries, and between general and special collections, etc., etc.). I tend to use terms like ‘cultural heritage’ or ‘cultural data’ to intentionally include a range of institutions that collect and share any sort of historical, artistic or scientific artefact or object, but sometimes that risks eliding important differences between museums, libraries and archives, including how and why their collections were formed and catalogued. Just as a ‘visit’ to a museum is different than a visit to a library, so the outcomes, challenges and opportunities for open cultural data are different.

Open cultural data at its simplest is data – images of or descriptive metadata about historical, scientific or cultural items – that is freely available for re-use (avoiding messy issues of commercial and non-commercial uses). But not all data is created equal – catalogue records without images might be the mainstay of collections management systems, but putting them online won’t in itself immediately serve a wide audience. Images of artworks lend themselves to a wider range of aesthetic responses and are more easily understood or re-purposed than images of social history objects. A digital image of a book cover or binding might be useful to scholars, but digital images of the pages, or even better, automatically-transcribed text from those pages, is useful to a wider audience.

The challenges are changing – there used to be resistance to sharing data online because staff feared it would lead to fewer visits to galleries or museums. Simultaneously, some feared that putting records online would lead to an increase in enquiries about the items (in reality, this was the more likely outcome). For museums, it’s increasingly clear that access to digitised versions of objects or artworks increases interest in the original, and probably increases the chance that they’ll visit it when they can. Open cultural data can help make collections more discoverable – a small museum or library mightn’t have much clout on Google, but their images might be encountered by tens of thousands on a Wikimedia article.

A long-standing concern is the impact of freely sharing material that could be monetised by picture libraries and other projects. Good digitisation requires decent metadata and technical infrastructure, which isn’t cheap when it’s done to the standards heritage institutions rightly require, but many people find commercial digitisation models problematic.

The opportunities for open cultural data range from the mundane to the aspirational, providing access to information and to experiences.

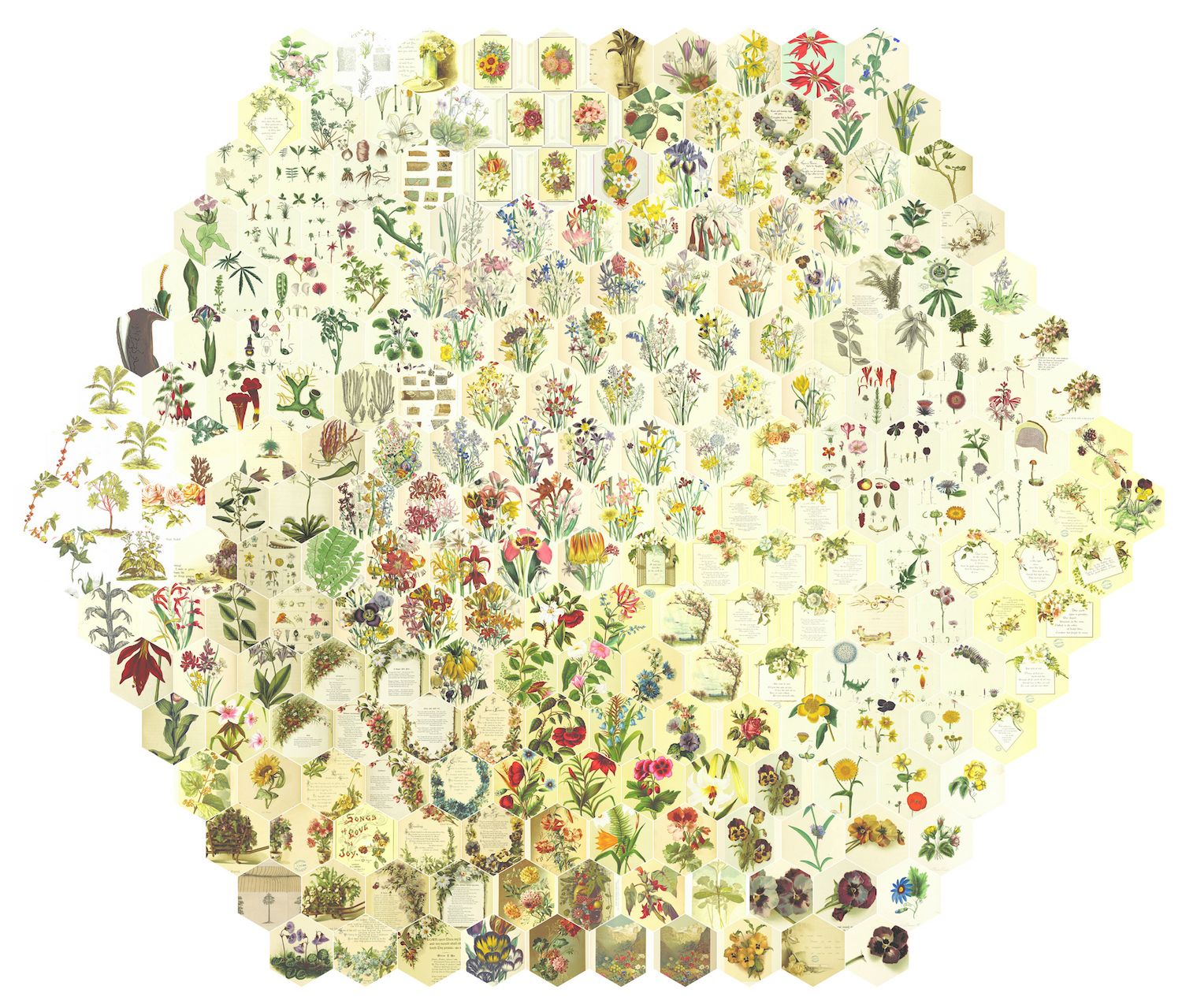

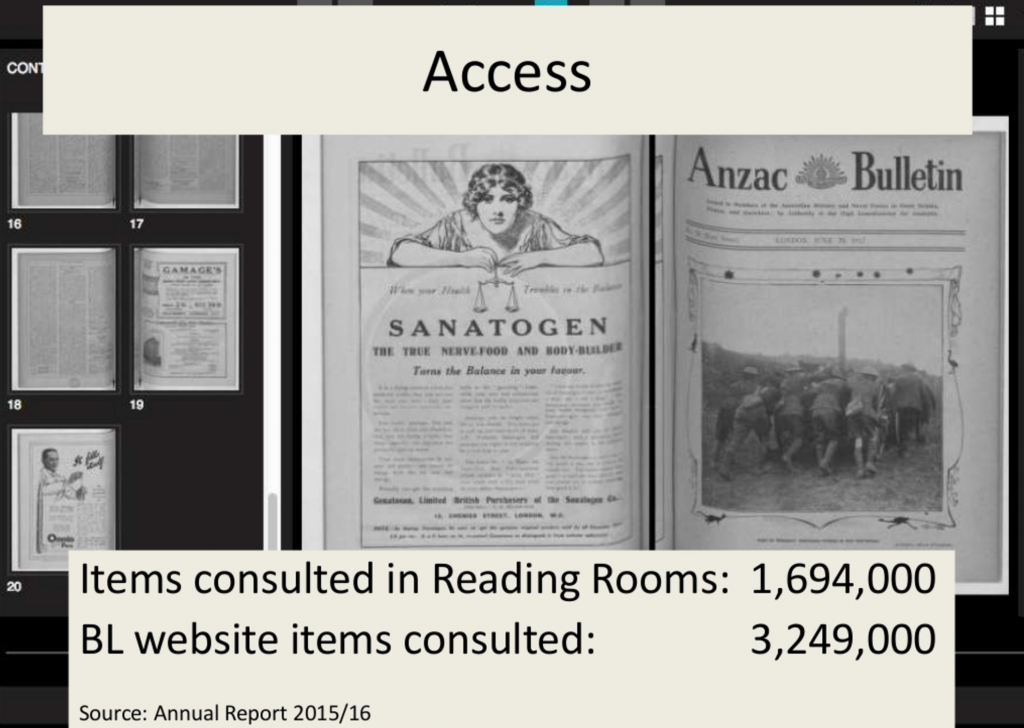

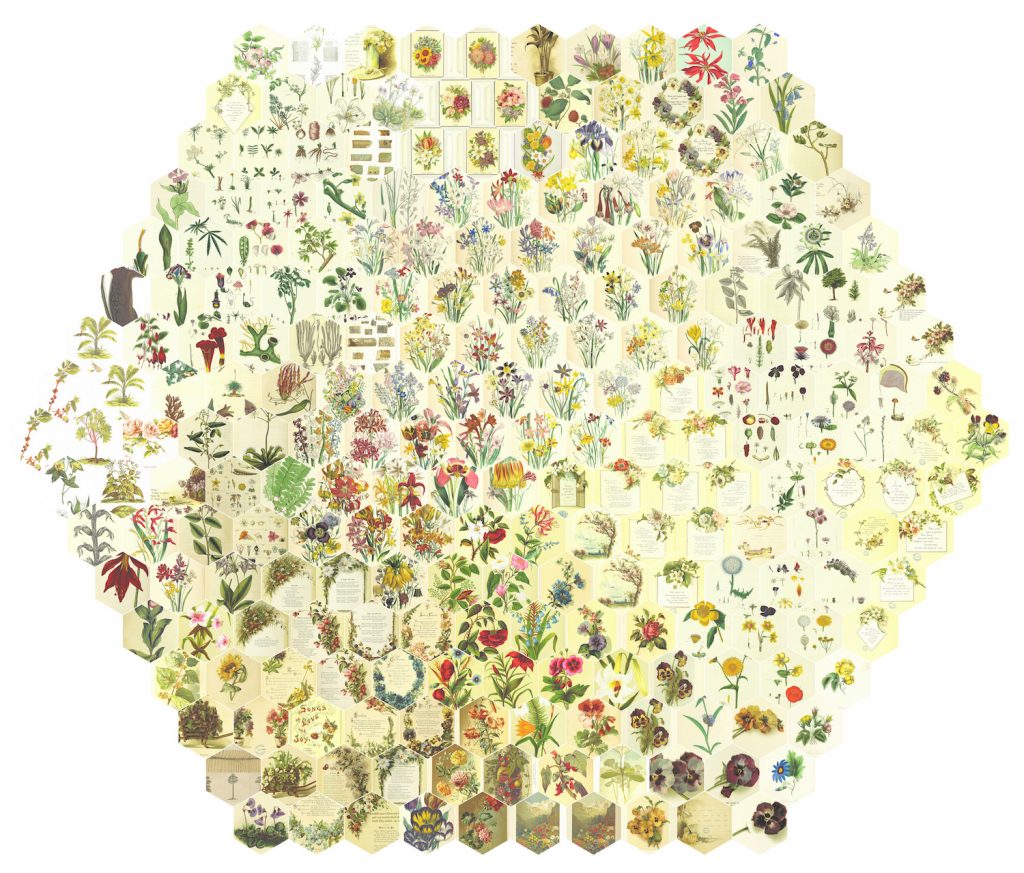

[pullquote] . . . numbers don’t tell the whole story.[/pullquote] Digitising books reduces pressure on the reading rooms and simultaneously makes them available to anyone anywhere in the world with a decent device and internet connection, at any time of day or night. Images from nineteenth century books uploaded to Flickr have inspired pop videos, art installations, generative artworks and who knows what scholarly curiosity. Which is a good reminder that tracking the use of open collections is itself a challenge, but have libraries ever really known what people do with the books they access? We get hung up on the number of people who access collections online, but numbers don’t tell the whole story. With any luck, at least some of them are acting as intermediaries who will provide further experiences of collections through traditional scholarly publications or fancy apps or something you can buy on etsy.

Thomas: I note that this is far from the first interview you’ve taken part in. What is one question you haven’t received that you would like to answer? What would your response be?

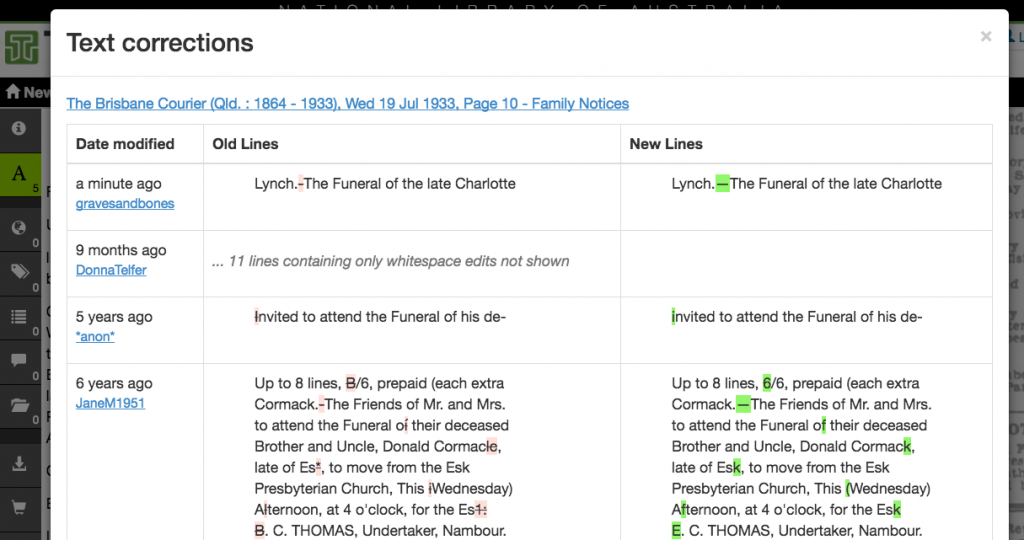

Mia: I tend to be asked about crowdsourcing a lot, but my doctoral research on ‘Making Digital History’ included an examination of the ways family and local ‘amateur’ historians have collaborated to create digital resources. These community history projects are rarely shiny or trendy, but they’ve set the scene for more formal aggregation and digitisation projects. I’d love people to ask what their organisation could do to support non-academic groups using their collections. Should anyone ask me, as a user experience researcher I’m contractually obliged to give the answer ‘it depends’ then suggest they find groups who are already using or have expressed interest in their collections and ask them. Their responses, in turn, might be as simple as ‘provide meeting space’ or ‘license material for re-use’ to ‘provide access to internal specialists who can answer questions about collections.’

Thomas: Whose data praxis would you like to learn more about?

Mia: Throwing the ball back over the Atlantic, I’d love to hear from Effie Kapsalis or Meghan Ferriter, who have done outstanding work on open access data and crowdsourcing respectively while working within the Smithsonian. Closer to home, I’d love to hear from Wellcome’s Jenn Phillips-Bacher, who seems to be at the heart of their innovative explorations of digital collections.