Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez is Processing Archivist for Latin American Collections at Princeton University Library. Elvia holds an MLIS with a concentration in Archives, Preservation, and Records Management from the University of Pittsburgh. She has presented widely on digital archives and diversity and is co-author with Rose L. Chou, Jenna Friedman, Simone Fujita, and Cynthia Mari Orozco of the forthcoming article ‘The Reach of a Long Arm Stapler: Calling in Microaggressions in the LIS Field through Zine Making’ (Library Trends, Spring 2018).

Thomas: In Invisible Defaults and Perceived Limitations: Processing the Juan Gelman Files you describe how technologies used to work with digital collections can channel bias – bias that is not just a historical legacy but very much a product of the here and now. Before we discuss this piece in detail I’m curious to hear more about what experiences shaped how you see your work in archives? Perhaps what led you to the archival profession?

Elvia: My interest in archives evolved from my studies in art history as an undergraduate at UCLA. I took a class on Dada and was fascinated by the Dadaists’ tendency to collect and piece together meaning from disposed and/or re-purposed materials. Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelor’s Even, The Large Glass and Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau inspired a deep pathos that eventually became the catalyst to move to a career in archives.

1921

To provide a little more context on the catalyst—between 1923 and 1936, Schwitters collected and progressively pieced together his colossal Merzbau with objects gifted or left behind by friends and family such as souvenirs, letters, clippings, and articles of clothing (some stolen by Schwitters). Everything that mattered to Schwitters became part of the bau. It was ultimately destroyed by an Allied air raid during World War II. Schwitters’ loss struck a chord with me. His unconventional way of record keeping and memory construction made me curious about archival collections and the process of maintaining and making them available for access.

[pullquote]Who gets to be remembered and historicized by way of record creation?[/pullquote]Archival work requires an ethics of care for the deeply personal and the deeply political. My former boss at the Center for the Study of Political Graphics often said that all art is political. The same can be said about archives and archival work. Record creation, keeping, obstruction, or misrepresentation are all acts of identity and power. Who gets to be remembered and historicized by way of record creation? Who is forgotten or purposefully silenced in history by way of omission or destruction of records? How are records themselves (official records created for governmental purposes in particular) used to communicate misguided notions of holistic representation, truthfulness, neutrality, and objectivity? These are all questions that initially drew me to and continue to keep me in the profession.

Thomas: I’ve noticed that power and representation or lack thereof are taking a more prominent place in Digital Humanities and digital library conferences. I gather that this focus in archival work isn’t necessarily sparked by a transition to digital environments – rather that it predates that transition and maybe even runs alongside it. Do you think there is a reciprocal value to be gained from working across physical and digital legacies? What sorts of critical questions are raised when working with either? How are these questions different or similar depending on the medium and the technology?

Elvia: Issues of representation and power are fundamentally rooted in archival work and there is rich critical scholarship that discusses these issues in the context of pre-digital archives. Sam Winn’s piece The Hubris of Neutrality in Archives does an excellent job acknowledging some of the recent critical work in the archival profession that addresses issues of representation, and gives a nod to Howard Zinn’s seminal address to the profession at the 1970 Society of American Archivists meeting. Scholars like Verne Harris, Cheryl Beredo, Randall Jimerson, and Michelle Caswell discuss issues of power, representation, and accountability by challenging the existing canon of archival neutrality and objectivity; speaking on colonialism, apartheid, and transitional democracies and their relationships to record keeping; and connecting these challenges to current archival practices. These scholars have built critical foundations for emerging scholarship that speaks to these same issues in the digital realm.

There is definite value to be gained from working across physical and digital legacies. The work helps us recognize our shortcomings. Jarrett Drake has pointed out that the archival profession’s canonical principle of provenance is grounded in a 19th century colonialist and imperialist era wherein legal property and ownership of records was limited to western white men. Historically provenance has more or less worked well for archivists tasked with keeping a history of ownership. In digital mediums and environments things are a bit different. What does the provenance of a collaboratively created or anonymously created Google Doc look like? In digital environments provenance is becoming increasingly difficult to pin down. I believe this will force the profession to re-evaluate how archivists should account for ownership, authenticity, and custody.

[pullquote]Appraisal for digital collections is, I believe, slowly being shouldered by the processing archivist…[/pullquote] Of course privacy and volume are issues present in analog collections but they are further problematized when we consider the digital deluge and the responsibility of determining permanent historical value. In analog archival collections donors and creators can physically comb through and filter materials they do not want to deposit in an archival repository due to the presence of sensitive or personal information. Acquisition of entire hard drives makes appraisal for donors a lot more difficult and places the responsibility of protecting sensitive or personal data on archivists, who, on the whole are not nearly paid enough; not equipped with the necessary tools and infrastructure; and do not have enough hours of the day to devote the labor necessary to peruse every file. Appraisal for digital collections is, I believe, slowly being shouldered by the processing archivist without a donor, curator, or administrator understanding of the amount of time it takes to do the work. Questions about how to best address privacy issues and what to keep and what not to keep when we speak with our donors at the point of acquisition is something archivists will have to continue to advocate for.

Thomas: At the end of your previous response you allude to what might be called “the weight of inheritance” – what is passed to us and the wherewithal we gather deal with it. I sense a similar tension at work in Invisible Defaults and Perceived Limitations: Processing the Juan Gelman Files. In that piece you describe how tools you inherit as an archivist carry a set of assumptions that bias processing and representation of digital collections. Are there particular strategies for recognizing these biases and dealing with them? Particular readings or frameworks that guide you in the engagement?

Elvia: I recommend taking a deep dive in social justice and decolonizing technology readings (a trove of which are located here and here).

For me, it has become important to recognize that the tools archivists and other information managers are using (and developing) are part of a larger system that is complicit in propelling and replicating a hegemonic Global North. While technologies are marketed as decentralized, democratic products unbound by location (geographic, cultural) they are largely being developed by a relatively small minority of the world’s population who has the majority control to assert autonomous power. Understanding this, we begin to ask how this frame of thinking impacts an archivists’ responsibility to collections on the margins of, or far from, the Global North.

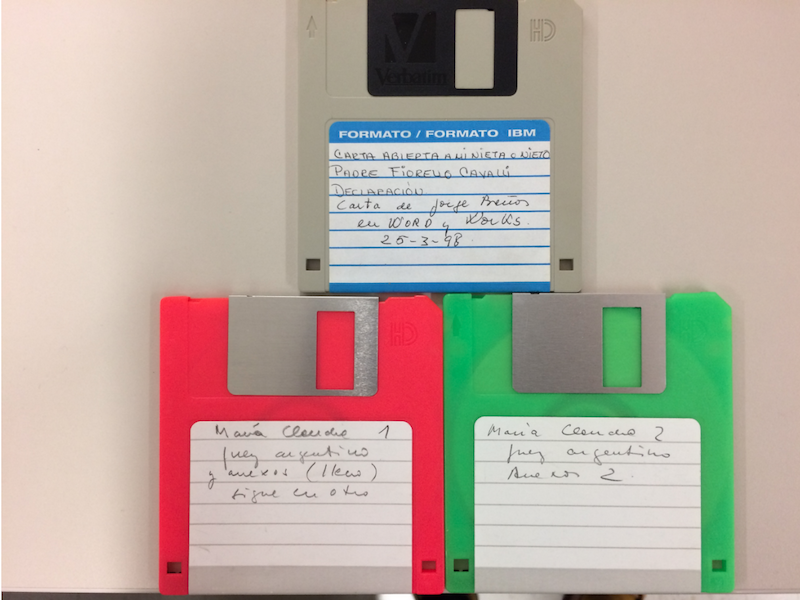

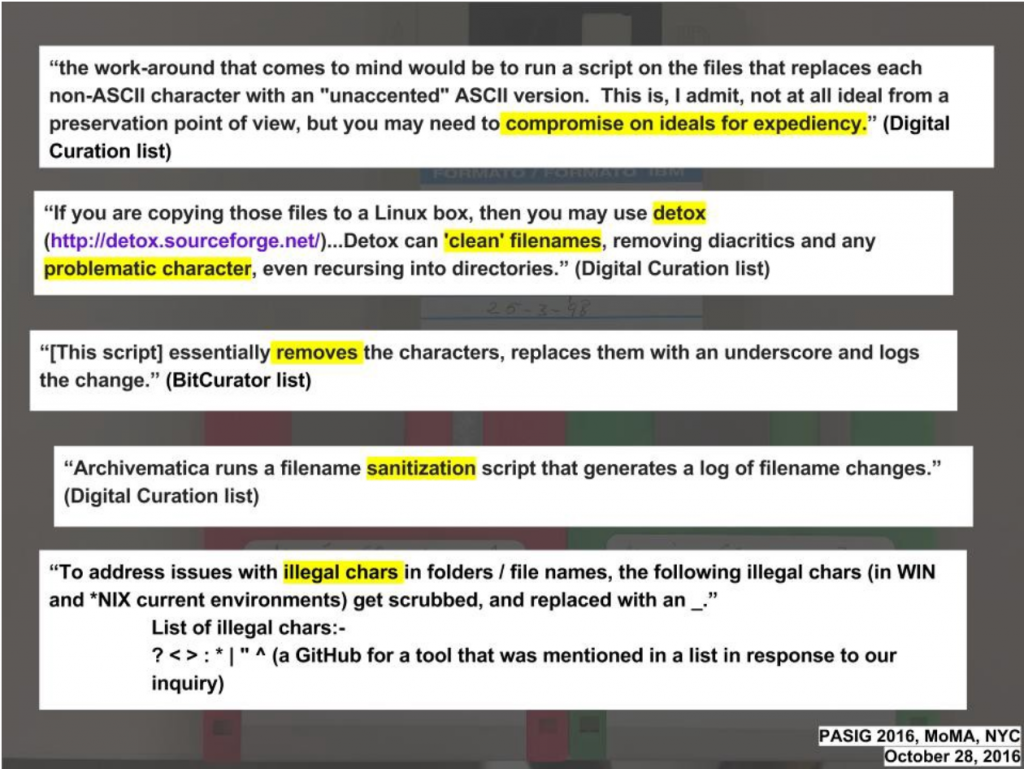

I want to emphasize that at the heart of what I was writing about in my experience processing the Gelman materials has more to do with recognizing our own biases and perceptions as practitioners learning to be technologists, rather than the current tools we have at our disposal.[pullquote]I also think about the weight of our ancestral and cultural inheritances and how we reckon (or not) with these as practitioners, users, and creators of digital collections. [/pullquote]You mentioned “the weight of inheritance” in the first part of your question — and beside having to reckon with the tools we use and their probable limitations, I also think about two other types of inheritances. I think about the technical language the digital curation community has inherited or adopted as its own and how potentially ill fitting it can be when applying it to cultural heritage collections. I also think about the weight of our ancestral and cultural inheritances and how we reckon (or not) with these as practitioners, users, and creators of digital collections. Tapping into my own cultural inheritances as a bilingual-U.S. living practicing archivist of Mexican ancestral roots, I understood how removing diacritic characters from accented words not only inherently changed the meaning behind filenames, it would be an act of cultural erasure. We need more use cases like Gelman’s in order to critically reflect on our current practices to make them better.

Thomas: In the digital humanities, researchers and practitioners (myself included) often dig into the language that is used to describe data and how one works with data. Verbs like cleaning (see Katie Rawson and Trevor Muñoz’ piece Against Cleaning) are problematized. The word data itself is questioned extensively – some even go the route of suggesting alternative nouns (see Johanna Drucker’s argument for capta). Some question a terrestrial bias at work in our understanding of data (see Melody Jue’s Wild Blue Media: Thinking through Seawater). An increasing number of scholars explore the genealogy of the word data (see Lisa Gitelman’s Raw Data is an Oxymoron). In your work with the Gelman files I was intrigued to see your focus on words like “clean”, “compromise”, and “illegal”. I’m wondering if you might comment on possible alternatives in this space? Maybe models of collaboration and community that could lead to something that better approximates the diversity of a range of lived experience?

Elvia: I find the use of the term “illegal” irresponsible when it is applied outside the confines of the law. Contextualizing the term in our current sociopolitical moment and its application (among others) in the form of a noun to describe migrants not authorized to stay in their country of residence makes for a potentially dangerous association with the dehumanization of migrants. We (digital humanists/archivists) are in the business of preserving and making accessible collections that include a diversity of cultures, identities, and perspectives. Surely we can find more accurate descriptors to communicate what checks out or does not check out in the language we use to describe our practices.

[pullquote]… we should keep in mind that wholesale adoption of technological language that has been developed for and by other (dis)similar fields is potentially incongruous to our needs.[/pullquote]Katie Rawson and Trevor Muñoz are onto something when they point to the example of “data cleaning” and how this term is used as an opaque shorthand for a number of diverse actions and steps that are taken to render data usable. This work illustrates the point that emerging areas of work in this space have not fully developed the pointed language needed to communicate our processes and roadblocks. As we move forward we should keep in mind that wholesale adoption of technological language that has been developed for and by other (dis)similar fields is potentially incongruous to our needs. Even in my use of “our” (digital humanists/archivists) there are varying use/need cases.

I believe having conversations across similar fields with a diversity of practitioners is key to understanding how our practices and end goals are alike and dissimilar. Part of the issue is that we are so busy trying to figure out how to reach end goals that we are not quite familiar with the practices each of us employ en route. The proposal of the Collections as Data framework is certainly an opportunity to bring together varied practitioners and users of data to conceptualize or begin reimagining a shared terminology that is mapped to our respective practices and responsibilities.

The records continuum model may add to the collections as data conversation. The model was originally conceptualized to reflect the overlapping responsibilities of records managers and archivists but I think it could potentially be expanded for those working on preserving and researching archival data. For instance, my goal as an archivist is to make little to no changes to the structure and content in a collection while normalizing accessible content to make it as platform and system agnostic as possible. When I intervene (duplicate or irrecoverable files, etc.), I must document and justify why I had to. These decisions should be made transparent to our users. The goals of digital humanists are a lot more diverse (i.e. potentially a lot more “data cleaning”), but their ability to access the content they work on is potentially dependent on my labor to preserve and provide access to it.

While archivists and digital humanists might have different goals, we share similar processes and terminology. I think the records continuum model can reveal how much of our current practices we share, or potentially want to share. I would love to organize a think out loud meeting (a future Collections as Data meeting?) with data curators, archivists, digital humanists, systems administrators and developers, and whomever else is heavily thinking about this. We might create a shared lexicon that better describes our shared needs and practices.

Thomas: Lastly, whose work would you like people to know more about?

Elvia: Tara Robertson’s presentation, Not All Information Wants to be Free, taught me that the library profession’s blanket tendency to digitize pre-Internet print resources can be harmful especially if it clashes with the original consent of participants involved. In the case Tara highlights, materials from an underground print publication that was produced for a very specific target audience were digitized and made accessible to a general audience without taking care to reach out to individual participants to get their renewed consent. The act of digitizing for access, in this case, was an act of “outing” for some participants who relied on the relative obscurity print provides. Everyone should take pause and read it.

Angela Galvan’s Architecture of Authority helps explore the differing and often conflicting core values libraries and vendors have and how these relationships affect the ways we provide access to our resources. The piece also complicates how we see our relationships to our users. My fellow co-presenter, Giordana Mecagni gave an excellent talk, The Colonizing Gaze – Digitized Collections, Radical Communities and Paywalls, on this subject at this year’s Society of American Archivists annual conference. Designer Jen Wang’s Now you see it: Helvetica, Modernism, and the Status Quo of Design, speaks on the history of design and its perpetuation of whiteness as aesthetic neutrality. Todd Honma’s work on teaching community archives and zines can serve as lessons for librarians, archivists, and other information professionals on how to use zines, an originally analog medium, to better engage with broader communities. I’ve gathered much inspiration, perspective, and validation from these readings. I am also excited to hear more from students and new professionals like Itza Carbajal, Chido Muchemwa, Nikki Koehlert, Aliza Elkin, and Crystal Paull, all of whom I just had the pleasure of meeting recently.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.