Laurie N. Taylor (Digital Scholarship Librarian) and Blake Landor (Classics, Philosophy, and Religion Librarian) profile recent DH developments at the University of Florida. These interconnected developments, including the formation of a dedicated library group, the development of a training course for librarians, and the launch of the Scott Nygren Scholars Studio, draw on related and distributed expertise across the campus.

Background

The University of Florida is a comprehensive, public, land-grant, research university, among the largest and most academically diverse public universities in the US. The UF Libraries form the largest information resource system in the state of Florida (the third most populous state).

Part of the history of digital humanities at UF is deeply connected with the UF Digital Collections at the George A. Smathers Libraries at UF. The UF Libraries have a long history of collaboration using technologies for preservation and access, including international collaboration for microfilming. In the 1990s, the UF Libraries began experimenting with digitization to preserve materials held in the Latin American & Caribbean Collections—collections that were built over many decades, through much collaboration with partner institutions—and in 1999, the UF Libraries formalized ongoing support for digitization by creating the Digital Library Center.

In 2006, the UF Libraries launched the UF Digital Collections (UFDC) using the open source SobekCM content management system. UF and partners collaboratively developed the SobekCM software to meet shared needs, including a robust socio-technical (people, policies, and technologies) infrastructure for:

- Digitization and digital curation (e.g., workflows, integrated tracking and reporting, integrated digital preservation); shared documentation; collaborative training programs; online tools for workflow needs including item creation, quality control, and metadata editing;

- Hosting for online access for all material types; integrated and separately aggregated per curatorial needs; specialized viewers for materials; branding; specialized supports for patron, scholar, librarian/curator, and other external and internal user groups; integrated online mySOBEK tools designed for general users, internal production users, and curators and scholars;

- Ongoing growth and development for needs related to institutions, collections, technologies, collaboration for growing capacity among all partners for new activities and for growing the collaborative community, new activities as with digital scholarship and data curation.

[pullquote]dLOC now has 38 international partner institutions, many scholar contributors, over a million user views each month, and is one of the largest Open Access collections for the Caribbean.[/pullquote]

SobekCM also powers the Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC), for which the UF Libraries are one of the founding partners and the technical host partner. Started in 2004, dLOC now has 38 international partner institutions, many scholar contributors, over a million user views each month, and is one of the largest Open Access collections for the Caribbean. dLOC partners digitize materials, curate collections, and collaborate with scholars on intellectual infrastructure, context, growing and supporting Caribbean Studies, and new research initiatives.

By 2011, thanks in large part to the community and collaboration with programs like dLOC, the UF Digital Collections boasted rich content and rich repository features supporting direct library needs and DH projects.[1] With the UF Libraries’s robust technical infrastructure, experience with collaborative projects, and a critical mass of digital library content, the UF Libraries recognized that the next steps required additional support to enable the UF Libraries, UF faculty and students, and others to grapple with ways of answering what do you do with it? and what next?

Answering these questions required changes in the socio-technical infrastructure for the human infrastructure in terms of positions, responsibilities, and organization. Within the existing structure, more steps were needed to build towards a comprehensive approach to address the place of subject and liaison librarians with data and DH. It was at this point that the UF Libraries created the Digital Humanities Librarian position from a Digital Projects Librarian position within the Digital Library Center. In 2012, the DH Librarian position moved to the Scholarly Resources & Research group, reflecting the growth and changed focus from curation as part of production to part of research services, with a closer alignment with Subject Specialist/Liaison Librarians. The past and unfolding history of the UF Libraries in supporting DH continues to grow and connect with digital library activities and related work, including in data curation.

In 2013, dedicated and specific supports for all UF librarians for DH were not in place. The Digital Humanities Library Group began in 2014 as a direct outgrowth of UF’s Data Management/Data Curation Task Force (hereafter, DMCTF), a group with many campus representatives and a campus-wide scope.

Data Curation Task Force and Digital Humanities Library Group: Subject/Liaison Librarian Roles

The DMCTF was established in 2012 to address the needs of researchers on the UF campus for a coordinated approach and culture of support for data curation and management across disciplines (DMCTF Charge). The DMCTF has been responsible for sponsoring data-related events, making policy and procedure recommendations for developing human and technical infrastructures, providing information resources for the university community, and fostering collaborations and developing a full culture of support.

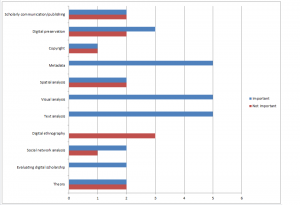

One of the DMCTF’s first recommendations was that Subject or Liaison Librarians develop a basic level of data literacy involving the skills necessary to effectively locate, analyze, manage, and interpret datasets, including (at a basic level) knowledge of data lifecycles; local and long-term storage options; knowledge of the DMPTool; awareness of data usage and practices in assigned subject areas; and awareness of tools and experts on campus to assist with data management for making appropriate referrals. At a more advanced level, the DMCTF recommended that Subject or Liaison Librarians have familiarity with analytical, statistical and visualization techniques and software.[pullquote]One of the DMCTF’s first recommendations was that Subject or Liaison Librarians develop a basic level of data literacy.[/pullquote]

The DMCTF was designed as an integrated group connecting other data activities and groups to enable full, campus-wide support in part by fostering a culture of radical collaboration. Although the DMCTF was somewhat too blunt an instrument to address the specific needs of digital humanists, especially in the development of training programs that centered on digital humanities, it was designed to be able to incubate new groups if appropriate. Two representatives from humanities disciplines sit on DMCTF: Laurie Taylor, Digital Scholarship Librarian (formerly called the “Digital Humanities Librarian”) and Blake Landor, the Classics, Philosophy, and Religion Librarian. Laurie is co-chair of DMCTF.

Laurie and Blake, authors of this post, discussed forming a separate, library-based group which focused on skills that library faculty and staff (especially Subject or Liaison Librarians) require to be effective supporters of digital humanities programs on campus as well as potentially involved themselves in digital humanities projects. We agreed that this group should function independently of DMCTF, while reporting back to DMCTF as input to policy recommendations. That conception was the origin of UF Libraries’ Digital Humanities Library Group (DHLG). Over the Winter Break this idea was developed into a proposal and submitted to the Library Administration; it was approved on January 29, 2014.

The DHLG was created without a specific charge other than to address/discuss issues in digital humanities and to schedule training in support of the group’s members. While the formation of the group was approved by Library Administration (with Blake in the role of Chair), it is very much a grass roots cohort of primarily Subject or Liaison Librarians brought together by a common interest. Laurie’s role has been as the administration liaison to the group as well as co-coordinator.

Shortly after the proposal was approved, an invitation to join the group went to the UF Libraries’s “All Librarians” email list and other email lists. Between 15 and 20 librarians and staff members responded to this invitation with the strong support of their supervisors to take the time off their normal schedules. The group participants include librarians and staff from various departments, including Special & Area Studies Collections, Humanities and Social Sciences, Fine Arts, Cataloging, and Administration. Since February, the group has met approximately every three weeks to discuss issues in digital humanities librarianship and define/plan a training course that would focus on digital humanities. As a model for our group to consider, Laurie developed a series of training modules or units that comprised the basic skill sets that our group agreed would give us a start on becoming well-rounded digital humanities Subject Librarians.

The Scott Nygren Scholars Studio

While this was taking place, two exciting, related developments occurred that reinforced the importance of what we were doing. The first was that UF Libraries’ Dean Judy Russell encouraged the group to explore the implementation of a Scholars Studio in our Social Sciences and Humanities Library (Library West). Dean Russell suggested that our newly-formed DHLG look into this idea and work up a proposal. We called an outside expert, Alex Gil, Digital Scholarship Coordinator at Columbia University Libraries, who provided recommendations and suggestions, including recommending a Scholars Studio model with a BYOD (“bring your own device”) environment that would offer wall paint, projector, and tables forming a collaborative space for instructional activities and collaborative projects, and a staging area for digital humanities-related presentations and events.

With strong internal support and sponsorship, DHLG participants organized a subgroup to develop the proposal. The subgroup added to the basic design, identifying use cases that demonstrated the value of a LED multi-touch screen, a “smart” podium, and inviting furniture, in addition to the updates to transform what is currently a rather traditional classroom into a flexible studio space. In response to input from academic departments, we added three computers with dual monitors to the proposal, and by April our completed proposal for a Scholars Studio was approved by the Library Administration, and named as the Scott Nygren Scholars Studio.

DH Library Group and Developing Librarian Program: DH and Subject/Liaison Librarians

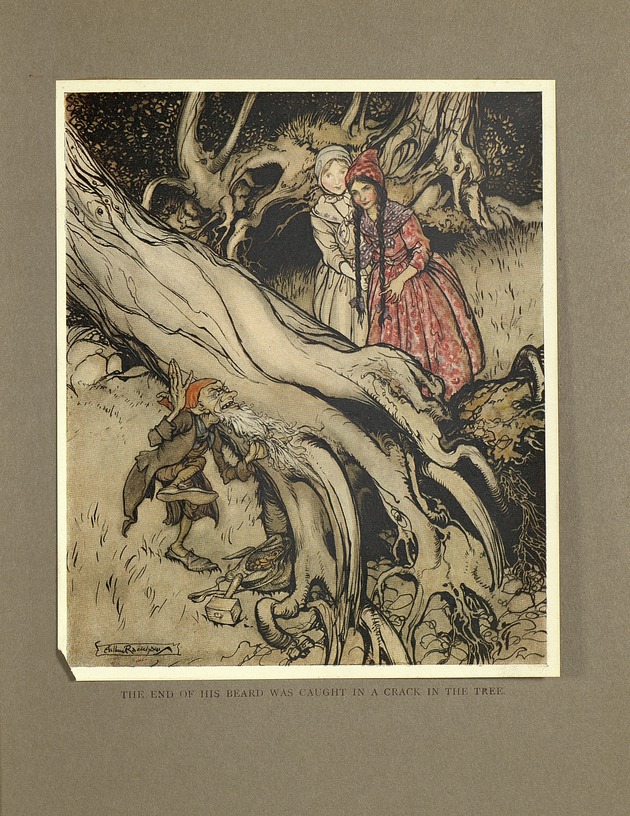

In addition to giving us advice about UF’s Scholars Studio, Alex Gil also shared some of his experience coordinating Columbia University’s Developing Librarian Project, which turned out to be the inspiration for the training program that the DHLG decided upon. The DHLG was especially convinced by the idea that training should not take place in a vacuum, but should rather be part of a collaborative project designed to improve library resources. The “learning by doing” motif has now formed the basis for the training program that DHLG devised. After much discussion, we decided to work on the curation of the Grimm Brothers’ Fairy Tales digital collection, a sub-collection of UF’s Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature collection.

In order to implement the Developing Librarian model, we drew on internal as well as external trainers, and applied for a library Mini-Grant in support of bringing in external trainers. The title of this one-year funding proposal, which references the Columbia University project, is “Developing Librarian Digital Humanities Pilot Training Project.” The proposed training schedule draws heavily on the training units that Laurie devised for our group and is centered on the curation of the Grimm Brothers’ digital collection as our specific focus. The grant proposal has been funded, with a funding period that will extend through June 2015.

The skill sets DHLG members hope to acquire with this pilot training project include, but are not limited to, project management and charters, content management systems (e.g. WordPress, SobekCM), TEI and metadata training, GIS, data mining and visualization, linked data, and online exhibit design and development. The overall program is being designed for participants to gain skills, experience, methodological knowledge, and confidence for learning new tools and for taking on leadership roles in initiating and collaborating on projects, developing training sessions for students and scholars, and addressing new needs as they emerge. Because DH is a growth area which potentially impacts a number of functional units in the library, and many departments outside the library, the wide interest in the DHLG’s training program is not totally surprising. However, not everyone who is interested in the training has time for the whole program, and so we are trying to make allowances to accommodate different needs.

From “Just in Case” to “Just in Time”

While the DHLG was getting started, planning was also underway for a graduate certification program in digital humanities. This idea started when Elizabeth Dale, Professor of History and Law, began working with the History Librarian, Shelley Arlen, on developing a digital humanities course for the fall of 2014, which includes a certificate upon completion of the course. A proposal to expand this idea to a graduate certification program in digital humanities is being worked on collaboratively by faculty members of the Departments of English and History, Laurie, Blake, and Shelley from the Libraries, and Sophia Acord, Associate Director of the Center for the Humanities & the Public Sphere. As a starting point, this program is leveraging courses currently being taught or in development. It has been instructive to learn during the early stage in the planning of this program the number (over 25) and variety of courses in numerous academic departments that offer digital humanities content. This is a fairly recent development and speaks to the timeliness of the new Scott Nygren Scholars Studio and developing librarian training program. When the DHLG proposal was submitted last January, to some extent we were in a “just in case” frame of mind (we need these skills just in case user demand for Subject Librarians with these skills ticks up). This has now turned into a “just in time” orientation; our training will be in full tilt just as the new DH graduate certificate program and the new Scott Nygren Scholars Studio are unveiled in the fall.

Thus, three separate concurrent developments at UF have been serendipitously dovetailing. Additionally, other work that builds from, informs, and connects to these developments includes activities to better formalize and support collaboration with Scholars Councils, across Florida with the nascent Florida Digital Humanities Consortium, integration and collaboration for teaching and research with the “Panama Silver, Asian Gold: Migration, Money, and the Making of the Modern” DOCC or Distributed Online Collaborative Course, and more.[2]

Being at the epicenter of several developments at their very inception and being closely connected and collaborating with many groups and individuals is an exciting place to be. We look forward to reporting back to this group in a few months, after these developments have had a chance to progress further.

[1] Other examples of digital humanities collaborations by UF Libraries

- Diaries of a Prolific Professor: Undergraduate Research from the James Haskins Manuscript Collection online and print on demand edited collection by teaching faculty librarians, archivists, and student researchers; written based on the experience of processing and working in the archival collection; the book represents a new scholarly contribution and serves as an artifact of the collaboration.

- Online exhibits, new Exhibits Coordinator, and Exhibitions Program: librarians have collaboratively created online exhibits with teaching faculty, students, and others from UF and beyond. In 2011, the UF Libraries created a new Exhibits Coordinator position to implement a full exhibitions program, which was necessary in part because of the consistently increasing in demand for collaboratively creating online exhibits as digital humanities scholarship.

- UF Digital Humanities Librarian and DH Program: In 2011, the existing Digital Librarian position title was changed to reflect the transformed position focus, from building digital collections to taking digital collections—including new digital collections—as foundations and critical components in the larger work of digital humanities, digital scholarship, data curation, and scholarly cyberinfrastructure. In 2012, the Digital Humanities Librarian position moved from the Digital Library Center, aligned more with digital production, to report through the Associate Dean for Scholarly Resources & Services which includes collections, positioning the DH Librarian and DH activities with Subject and Liaison Librarians.

- UF’s Digital Humanities Working Group (DHWG): UF’s DHWG began in 2011 when Sophia Acord, Center for the Humanities & the Public Sphere, and Laurie Taylor, Digital Humanities Librarian, jointly convened the inaugural meeting to discuss activities designed to build a community of practice at UF for exploring the humanities in and for a digital age. UF’s DHWG includes members from across campus, with many from within and outside of the UF Libraries.

- UF Annual Digital Humanities Day: UF’s DHWG hosted the 1st and 2nd annual UF DH Days in 2012 and 2013 saw over 120 people at each event, gathered enormously positive feedback from the post-conference attendee surveys, and abundant, positive anecdotes of new collaborations, projects, and practices from participants (2012 introductory slides and 2013 program materials) as well as several new DH projects like the collaborative grant with Museum Studies and Library faculty for “Archiving the Photographs of the First Transcontinental Railroad.” Perhaps most importantly, these events help support development of the DH community at UF.

- THATCamp-Gainesville: the 3rd UF DH Day event was THATCamp-Gainesville, the first THATCamp for UF and Gainesville in April 2014, which received positive post-event participant evaluations and positive anecdotes across such a great variety of areas (program materials). We don’t yet have clear examples of new projects or initiatives that can be directly traced to THATCamp-Gainesville, but the event brought together attendees from across Florida and allowed for the next-step discussions on creating the Florida Digital Humanities Consortium, with that creation underway.

[2] Related, Connected, and Intertwingled Activities

Some of the related current work, with more details, includes:

- “Forging a Collaborative Structure for Sustaining Scholarly Access to the Baldwin Library for Historical Children’s Literature,” a project by Suzan Alteri, Curator of the Baldwin Library, to develop a Scholars Council for the Baldwin to formalize support to growth collaboration among the Baldwin Library and its scholarly community.

- dLOC Scholarly Advisory Board Expansion, where UF is participating with the dLOC partners in developing plans for expanding the Scholarly Advisory Board (perhaps also having it become a Scholars Council) to best support and provide credit for the rich and abundant work already being done, and to support future growth.

- “Florida Digital Humanities Consortium,” with many institutions in Florida collaboratively planning the prototype or draft of the operational model to support the broad, rich, and deep collaboration and DH work in Florida. Discussions on statewide collaboration began at THATCamp-Florida hosted by the University of Central Florida and continued at THATCamp-Gainesville at UF. Now, UCF teaching faculty and UF teaching and librarian faculty are serving as core organizers for facilitating and launching the new initiative with the statewide community.

- “Panama Silver, Asian Gold: Migration, Money, and the Making of the Modern,” DOCC or Distributed Online Collaborative Course taught in fall 2013 by Rhonda Cobham-Sander with librarian Missy Roser at Amherst College, Donette Francis with librarians Beatrice Skokan and Vanessa Rodriguez at the University of Miami, and Leah Rosenberg with librarians Margarita Vargas-Betancourt and Laurie N. Taylor at the University of Florida. In designing the course, the scholars deliberately created the syllabus, modules, and teaching resources such that other teachers could easily use the materials to teach the full course or select specific lessons in the future with the clearly articulated goal to build intellectual infrastructure for Caribbean Studies by creating course materials, identifying materials for digitization, and creating new scholarly works with all added to dLOC (materials for teaching and research resulting from the course).

- “Piloting a Peer-to-Peer Process for becoming a Trusted Digital Repository:” the libraries of the University of North Texas and UF are collaboratively creating a pilot peer-to-peer process for TRAC to build towards becoming a Trusted Digital Repository, including using the process to build even stronger capacity locally and as a community for supporting collaborative needs related to preservation, governance, auditing, reporting, and other concerns.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

[wp_biographia user=”blaland”]

[wp_biographia user=”lntaylor”]