John Russell, of the University of Oregon Libraries, recently taught a new, graduate-level course in digital scholarship, which he introduced earlier on dh+lib. In this post, he reviews how the class went.

My Issues in Digital Scholarship class ended in March (we’re on the quarter system in Oregon). This class was designed to introduce graduate students in the Humanities and Social Sciences to digital methodologies. Hence, digital scholarship rather than digital humanities: I needed to appeal to an interdisciplinary audience. My focus was not so much on tools or technical skills, but on how scholars were applying these tools in different contexts, framed such that students could understand why and how they might apply these approaches to their own research or teaching. I also introduced students to metadata, digital preservation, and changes in scholarly communication in relation to the expansion of digital methods. As I argued in my post introducing the course: “This is an inversion of the digital scholarship ethos which has emphasized tools and making things, and very intentionally so.”

Among the DH-inclined faculty on campus, there was considerable interest in the course and its role in supporting (and encouraging) graduate student digital scholarship. Because of this faculty attention, I decided to ask the students for supplemental feedback in addition to the regular, university-sponsored instructor/course evaluation. The questions were designed quickly and without considerable planning, with the hope of obtaining results that would inform a broader conversation about digital humanities on campus and in the library. [pullquote]The questions were designed quickly and without considerable planning, with the hope of obtaining results that would inform a broader conversation about digital humanities on campus and in the library.[/pullquote]I wanted to find out whether students thought that a digital scholarship course should be offered regularly, perceived any special value to having it in the library, and preferred any particular topics (which were of most and least interest). Information about students’ preferred topics would also help me think about what parts of the syllabus were worth keeping and what might be jettisoned.

The students – in their evaluations and in their comments to me – were generally positive. The first part of the supplemental evaluation asked for responses to specific questions, scaling from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree):

- This course helped me understand current approaches to digital scholarship.

- This course helped me understand how to use tools for doing digital scholarship.

- This course made me want to integrate digital scholarship into my own research projects.

- There should be a course on digital scholarship offered at least once/year.

- The UO Libraries should offer a course on digital scholarship at least once/year.

Six out of the eleven students filled out the evaluation; most of the responses were in the agree-strongly agree range, with two tepid responses to question 2 (I learned how to use DH tools) and one shrug to question 3 (this course makes me want to do digital scholarship). Since the course was designed to emphasize approaches to digital scholarship over learning specific tools, the responses to the first three questions make sense. Additionally, all of the respondents strongly agreed that a similar course should be offered every year, and they mostly strongly agreed that the library was a good place to do it.

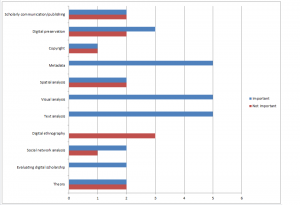

I also asked the students to select the most and least important topics covered in the course (click to enlarge):

The big favorites were metadata, text analysis, and visual analysis. The evaluation also included an open-ended question about topics students would like to see spun off as a standalone course or workshop. Of the three responses, two indicated an interest in text analysis, and one asked for digital preservation. The repeated mention of metadata surprised me and I’ll have to do more with it next time (it was covered in a session along with copyright and digital preservation, just a bit of discussion without any work on examples). It is possible that the pro-metadata contingent was thinking specifically about TEI, as three of the students from this class went on to do a readings course with me on TEI in the Spring term (we worked through the TEI Guidelines by encoding examples of different types of text: prose, verse, drama, manuscript).

None of the above is particularly scientific (nor is it intended to be). But the responses do suggest areas to tweak in future versions of the course. I’ve already decided to focus more explicitly on texts and digital humanities. Covering lots of bases was good from a survey perspective, but I got the feeling that students wanted to dig into things more deeply and realized that I, too, would benefit from sustained attention to a coherent set of tools and scholarly discussions. [pullquote]Covering lots of bases was good from a survey perspective, but I got the feeling that students wanted to dig into things more deeply and realized that I, too, would benefit from sustained attention to a coherent set of tools and scholarly discussions.[/pullquote]

Also, while I initially spun the course as digital scholarship and as a broad survey to appeal to those students from non-Humanities disciplines, doing so meant trying to make every topic as relevant to a Journalism student as it was to a Literature student. This created a lot of extra work for me as I tried to be all things to all people, but also stunted conversation: for example, if the Lit students wanted to take discussion in one direction, some of the other students would withdraw because it wasn’t an avenue that was meaningful to their scholarly situation.

Clearly, the experience of teaching the course and mulling over the student evaluations have tempered my original antipathy toward a digital humanities pedagogy centered on tools and making things. While I still believe that sustained attention to current scholarly practice is an important part of graduate training, I recognize that students also wanted, at the very least, some guided play so that they could develop their own sense of what the tools can and cannot do, something akin to the practical context that Columbia’s Developing Librarian Project made central to their program. I am working on adding a lab component to the course so that there would be dedicated class time for engaging tools, with the labs organized to develop a project (like mapping newspaper coverage of Modernist poetry).

My goal is to rework the syllabus over the Summer and when I’ve gotten to a good place with it, I’d love to share it here.