In this post, Thea Lindquist, Holley Long, and Alexander Watkins (University of Colorado Boulder) detail the multi-modal work that the University Libraries’ Digital Humanities Task Force undertook to actively assess digital humanities interest and needs on their campus, and to recommend models for library engagement.

Digital modes of teaching and research are steadily gaining ground in the higher education environment. Libraries, as central, interdisciplinary spaces on campus dedicated to advancing the research and teaching mission of the university, are playing a key role in many of the digital humanities initiatives that have been started at universities around the world. In recognition of the strength of this trend, a variety of initiatives are underway in the library world to meet this demand, acquire skills, and share expertise, for example, ACRL’s Digital Humanities Interest Group and the dh+lib blog you are reading right now. The many new position listings for librarians with digital humanities and digital scholarship responsibilities are a further indication of libraries’ commitment to partnering in this movement on their campuses. But how do we know what type and level of involvement might be most impactful for our own libraries and campuses?

The Impetus

In 2012, a group of librarians at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU-Boulder) were becoming increasingly aware that, while digital humanities was gaining ground on our campus, little in the way of centralized coordination and support for this work was available to the campus community. A handful of prominent scholars with well-publicized projects had been involved longer-term, for example, Lori Emerson and her Media Archaeology Laboratory; however, questions about incorporating digital modalities into research, teaching, and learning had started to emerge from graduate students, new faculty members, and established faculty members who had been hearing about them at disciplinary conferences. A previous campus Digital Humanities Initiative, which had participated in Project Bamboo meetings, unfortunately had failed to take root several years before.

[pullquote]Questions about incorporating digital modalities into research, teaching, and learning had started to emerge from graduate students, new faculty members, and established faculty members who had been hearing about them at disciplinary conferences.[/pullquote]

Though the library was a lead partner in the earlier initiative, little had been done after that group’s dissolution. The interest that surfaced recently was different in that it came from the grassroots – both from librarians and from campus researchers. The task force was formed at the prompting of a small group of interested librarians, History Librarian Thea Lindquist, Digital Initiatives Librarian Holley Long, and Art & Art History Librarian Alexander Watkins. In late January 2013, the Libraries Administration officially formed a Digital Humanities Task Force, which was charged with investigating and reporting on digital humanities activities and needs on campus and formulating recommendations for how librarians might partner with scholars and other units on campus to further digital humanities work. We initiated the task force by sending an open call for volunteers to the Libraries’ faculty and staff. Leo Arellano, Michael Dulock, Eric Harbeson, Erika Klein, and Esta Tovstiadi joined us on the task force, bringing expertise and perspectives from metadata, research desk services, acquisitions and collection development, and archives and special collections. To serve our goal of forging partnerships with other technology-related campus units, we asked two academic technology consultants from the Office of Information Technology (OIT), Viktoriya Oliynyk from the humanities and Jacie Moriyama from the social sciences, and the director of the Visual Resources Center in the Department of Art & Art History, Elaine Paul, to join the task force, as well.

Our Goals

The objectives of the task force were three-fold:

- to investigate the current state of digital humanities at CU-Boulder and develop a profile that elucidates researcher demographics; methodologies, services, and resources of interest; and barriers to undertaking digital work.

- to assess the need for a campus-wide digital humanities initiative at CU-Boulder.

- to evaluate models for funding, structuring, and staffing library-based initiatives at peer institutions.

In order to achieve these objectives, the task force collected a variety of data using multi-modal research methods upon which to base sound, evidence-based recommendations. Using this type of approach, researchers “collect and analyze data, integrate the findings, and draw inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study.”[1. Abbas Tashakkori and John W. Creswell, “Editorial: the New Era of Mixed Methods”, Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1, no. 1 (2007): 4.] Fidel Raya’s 2008 investigation found that only five percent of a sample of five hundred articles in library and information studies utilized mixed methods research, suggesting that it is not a very common approach in our field. This finding is certainly understandable considering the amount of work involved, but we found the benefits to be well worth the effort. Mixed methods research is ideal for complex and multi-faceted questions like those we were exploring and result in a richer data set. Additionally, triangulating results from the different methodologies created a consistency check that ensured our conclusions were well-founded.[2. Raya Fidel, “Are We There Yet?: Mixed Methods Research in Library and Information Science”, Library & Information Science Research 30 (2008): 266-267.]

[pullquote]Mixed methods research is ideal for complex and multi-faceted questions like those we were exploring and result in a richer data set.[/pullquote]

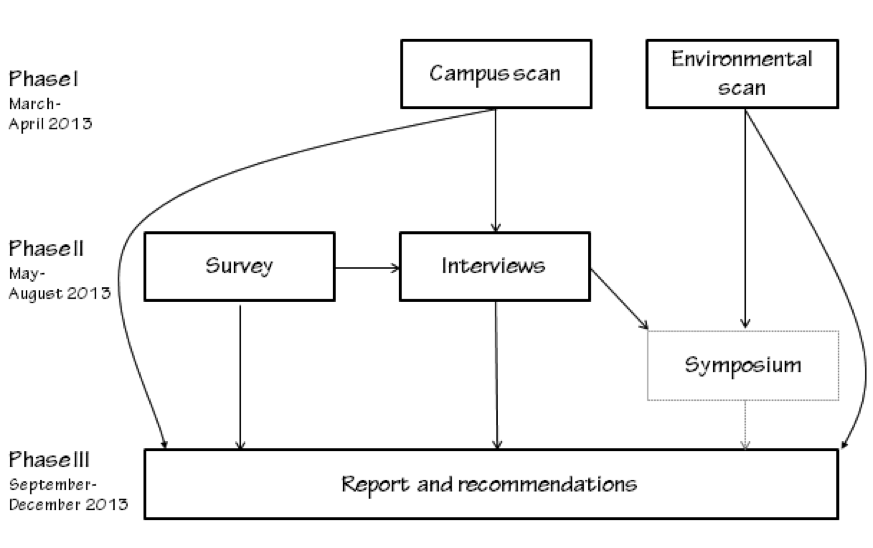

Our Multi-Modal Approach

Our research entailed six months of intensive work, including conducting internal and external environmental scans, a campus-wide survey, and one-on-one interviews. During this time, we also organized a symposium for CU researchers to showcase their digital humanities projects. We planned the work in three phases so that each would feed synergistically into the next. The campus scan and survey, for example, helped us to identify potential participants for the interviews.

In the early planning stages, the task force discussed its working definition of digital humanities at length and made a conscious effort to be as inclusive as possible. The definition was shared with interview and survey respondents to establish a common understanding of the nature of our inquiry. Our decision to take a broader view of digital humanities influenced the outcomes of our investigation in beneficial ways by encouraging us to make connections with researchers in all disciplines and opening up the possibility to envision a more comprehensive digital scholarship initiative.

In the first phase of our work, the task force divided into two subgroups to conduct external and internal environmental scans. The external scan subgroup consulted sources like the Association of Research Libraries’ (ARL) SPEC Kit 326: Digital Humanities and CenterNet’s International Directory of Digital Humanities Centers to create a list of institutions that host library-affiliated digital humanities initiatives. We reviewed these initiatives’ websites to collect data on offerings, staffing models, representative projects, funding, date of establishment, and usage statistics; however, information on the last three data points was scarce. The group identified more than twenty-five different types of support for research, teaching, and professional development. The five most common were lectures and symposia, workshops and training, collaborative work spaces, digital collections, and project management and consultation. Though data on staffing was incomplete, we noticed that all of the initiatives were staffed by more than one person and included a mix of librarians, teaching faculty, technologists, and student assistants. An advisory board including members from a variety of campus units often guided the initiative.

The group also collected statistics on budgets, staffing, collections, and size of institution from sources such as the ARL Statistics and LibQual. Interestingly, we found CU-Boulder was below average in staffing and total library expenditures, yet slightly above average in terms of the population served based on student enrollment numbers. Despite this, we noted that two of the institutions scanned had very similar statistical profiles and still managed to support robust digital humanities initiatives.

Working in parallel with the external scan, a second task force subgroup undertook an initial scan of digital humanities activities at CU-Boulder, with the goal of identifying associated people and projects as well as campus resources that were currently available for digital humanities work. Using a variety of keywords, we searched campus faculty profiles (powered by VIVO open-source software) to find individuals involved or potentially involved in broad range of digital humanities activities. The subgroup also investigated the websites of likely departments for digital humanities projects and for resources for conducting digital humanities work, such as specialized computer labs. We analyzed campus-wide offerings such as those provided by OIT (e.g., software, academic technology consultants, limited server space) to identify which could be of potential use to digital scholars. The information we gathered was intended to serve as the foundation for a centralized knowledge base of resources and services that could later be expanded and made available to the campus community.

After the internal and external scans were completed, at the end of April 2014, we went about directly querying our study populations through individual interviews and a campus-wide survey. Using these methods, we wanted both to talk in depth with digital humanists on campus and to capture information about emerging needs and interests. A task force subgroup interviewed seventeen faculty and three graduate students who were already incorporating digital humanities into their teaching or research.

We designed questions to gather information about the services, resources, and methodologies they utilize, as well as about barriers they encounter in undertaking digital work. We also asked how they monitor developments in digital humanities and about their cross- and intra-institutional collaborations. In addition to learning about digital scholars’ habits, we elicited their help in designing a support infrastructure by employing participatory design techniques. We asked questions about the single biggest problem that they would like to solve and what their ideal support network would look like. They also engaged in a drawing exercise to represent graphically their most recent digital project and mark areas where support would have been useful.[3. The interview questions are available in Appendix A of the task force’s report, “dh+CU: Future Directions for Digital Humanities at CU-Boulder”, which is available at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1_p_AH2mS1xFnAXxpPbG9N0xDHmvBjaNSAKrNQKVFOgU/edit?usp=sharing] Finally, in order to facilitate the identification of themes and trends in the data, we coded and analyzed notes and audio files from the interviews in NVIVO qualitative data analysis software.

In parallel with the interviews, another subgroup created a survey in Qualtrics, distributed in June 2013 to CU-Boulder faculty, graduate students, and post-doctoral researchers regarding their interest and involvement in digital humanities.[4. The survey instrument is available in Appendix B of the task force’s report. Please note there are three different tracks for those who are involved, interested, and not interested in digital humanities.] In keeping with the broad view of digital humanities activities that we intended to capture, we invited all members of these groups to respond, regardless of departmental or disciplinary affiliation. The survey went out to approximately 8,000 affiliates, and we received 345 responses from participants in programs, institutes, departments, schools, and colleges across campus. The greatest percentages of interested faculty were from the Libraries (16%), Journalism (12%), and Music and Education (both 10%). Among graduate students, Journalism registered the highest percentage of interest (12%). Survey responses proved an extremely rich and broad data source to inform our report and recommendations.[pullquote]We collected feedback from those who said they were not interested in digital humanities; the majority of these respondents explained that digital humanities work required too much time or was not applicable to their research.[/pullquote]

Through the survey, we collected a broad array of easily collatable and analyzable data directly from users, and reached a key group that other methods did not – those who were interested but not yet involved in digital humanities. We learned, among other things, in which campus departments, colleges, and schools respondents were rostered; in which digital humanities methods they were interested; what existing internal and external services and resources they use; and which they wish were available. Further, we collected feedback from those who said they were not interested in digital humanities. The majority of these respondents explained that digital humanities work required too much time or was not applicable to their research. From the data, we were able to generate customized reports for different audiences – for instance, a report on graduate students for the Dean of the Graduate School.

The Results

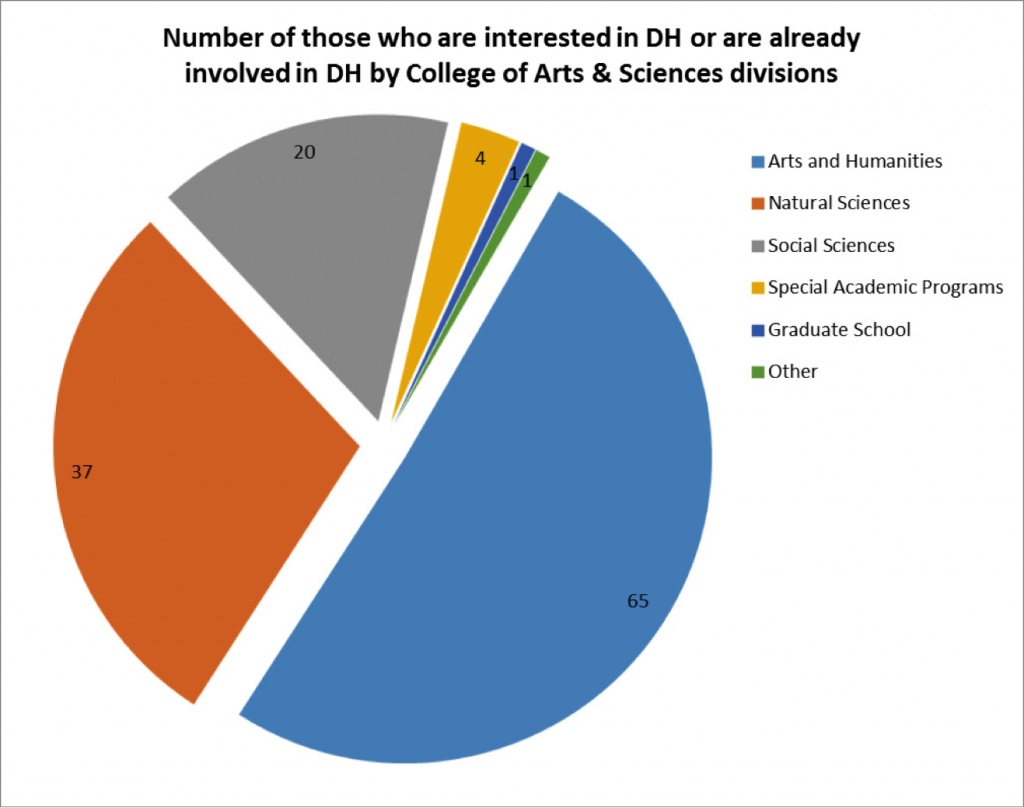

Multidisciplinary interest in digital humanities came across strongly in our survey data. While, as might be expected, scholars in the College of Arts & Sciences constituted the largest number of those who were interested or already involved in digital humanities, a significant number of scholars in the College of Engineering, College of Music, and School of Education also self-identified in these categories.

Digging deeper into results from the College of Arts & Sciences, Chart 1 shows that involvement and interest in digital humanities was strongest in the Division of Arts & Humanities, where 17% of faculty responded positively. The highest percentages were in the departments of History, French and Italian, Philosophy, Asian Languages and Civilizations, English, and Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures. However, faculty in departments across the divisions of Social Sciences and Natural Sciences were also interested in investigating humanities-related digital modalities. Disciplines that stood out overall for both faculty and student interest were History, Philosophy, English, languages and literatures, and Linguistics.

The demographics of the survey and interview data suggest that partnerships to support digital humanities across campus departments are needed and that siloing support networks — making resources available only to a limited constituency — could inhibit interdisciplinary collaboration. Community is especially vital to connect digital scholars who are rostered in disparate departments and colleges. Additionally, though interest on campus is high, more support and collaboration is needed to enable interested graduate students and faculty to become active digital scholars. The need is particularly great among graduate students, who may need these skills as they enter challenging job markets. Graduate students regularly contact us to provide experiential learning opportunities in this area.

The survey and interviews together revealed that faculty and graduate students are either engaged in or interested in employing a wide range of digital humanities methodologies in research and teaching. The most common were multimedia and digital publication (66%); image, audio, and video editing (53%); text mining (43%); digital writing and storytelling (35%); analysis of new or social media (34%); geospatial analysis (25%); machine learning and computational linguistics (23%); and gaming (15%). Of course the popularity of these methodologies varied by discipline. History, for instance, had the greatest proportion of respondents interested in geospatial analysis.[pullquote]Many faculty conflated digital humanities with the broader topic of educational technology.[/pullquote]

It was also clear that faculty and graduate student teachers were considering the possibilities that digital humanities holds for pedagogy. Sixteen of twenty interviewees indicated that they incorporate it into their teaching. However, many faculty conflated digital humanities with the broader topic of educational technology and discussed tools such as Google apps and Prezi, social media platforms, and the incorporation of online digital collections into lectures and assignments. Yet some were using technology in truly transformative ways, more consistent with digital humanities practice. For example, one English instructor incorporated the text analysis tool Voyant into her course discussions and assignments, and an Art instructor gave a sample assignment for which students were required to find sounds online, remix them for inclusion in a live performance in class, and then write a blog post about the performance process.

Analysis of the data indicated that graduate students are among the most ardent supporters of digital humanities and would very much like to see it integrated more fully into all aspects of academic life, including the classroom. Faculty perceptions of student interest in these methods and tools, however, were more evenly distributed on the spectrum from very interested to not interested. Faculty also observed that new technologies require a good deal of scaffolding to incorporate effectively into instruction, and that students can be ambivalent about expending the effort to learn them. In multiple contexts, faculty and graduate students both remarked that undergraduate students are less likely to draw a distinction between digital and traditional methods.

One of the task force’s main goals was to better understand digital scholars’ needs and the barriers that they encounter in their work. We also wanted to discover what support they desired in order to begin or advance their digital humanities work. What we found was that in many cases barriers and desires were closely aligned (see Charts 2-4 for representations of barriers as well as desired services and resources). The goal was to formulate recommendations that would mitigate or eliminate these obstacles and gaps. Thus both the interviews and survey asked digital humanities-involved respondents to describe the barriers that they face.

Respondents to the survey and interviews cited lack of technology skills and demonstrated a desire for technology training. This evidence strongly informed the task force’s recommendations. Unsurprisingly, digital humanities-involved respondents identified lack of time as a significant barrier. Interviewees pointed out that a significant time investment is required to become competent in the methodologies, conduct their investigation, and then perhaps integrate them into the classroom. Competing demands, such as traditional modes of scholarship, do not leave much time to explore, and narrow expectations about what types of research count in hiring, tenure, and promotion keep digital humanities on the back burner for many researchers. Our research suggests that scholars highly desire a framework for evaluating digital humanities activities for promotion and tenure.[pullquote]Digital humanities-involved respondents identified lack of time as a significant barrier.[/pullquote]

Survey respondents also pinpointed lack of funding as a major concern, and more in-depth comments from interviewees about funding proved useful for delving deeper into the issue. The most frequently mentioned theme was that they did not have access to adequate funds to initiate the many interesting ideas they had for digital research projects. They especially requested student assistants, course releases, and technology (whether programming, software, or server space). Secondly, for those initiatives fortunate enough to acquire grant funding, respondents noted that reliance on soft money is not sustainable. Our research suggested support such as fellowships, technology infrastructure, grants, and other funding sources are in high demand.

One of the major barriers to a full-fledged digital humanities ecosystem at CU-Boulder is the lack of a coherent community of practitioners. For those already involved in collaborative digital humanities projects, the majority were working with colleagues across departments at CU-Boulder, while about a third of partnerships were with colleagues at other institutions. These partnerships were very often interdisciplinary endeavors. Our interviewees desired a local community to link digital humanities researchers, particularly those with subject knowledge to those with technological expertise. The overwhelmingly positive response to the symposium as a networking event further underscored the desire for community.

While the lack of resources and support discussed so far is certainly a valid issue, the task force noted that in many cases respondents were not aware of existing resources and services on campus that might be helpful to their work. Thus referrals play a vital role in our recommendations.

Conclusion

By taking a multi-modal approach, the members of the Digital Humanities Task Force were able to present well-justified recommendations to the CU-Boulder Libraries and campus based on a holistic view of the practices of digital scholars as well as the challenges they face. In addition to our research activities, conversations we had with outside experts and campus administrators as a part of a campus-wide digital humanities symposium and workshop organized in August 2013 were influential in the task force’s final report and recommendations.[5. The experts – Trevor Muñoz (University of Maryland), John Unsworth (Brandeis University), and Katherine Walter (University of Nebraska–Lincoln) – delivered keynote addresses on the future of digital humanities in higher education, followed by CU-Boulder presenters showcasing their own projects. More information about the presentations is available here.] The connections we made during this process not only created momentum for digital scholarship activities on campus, but also sparked new collaborations between librarians, colleagues from other campus units, and researchers across disciplines. Lindquist, for instance, co-taught a graduate-level digital history course with a faculty member from the History Department. The department also recently hired an instructor whose job duties include acting as its digital liaison. Together with the incoming director of our Institute for Behavioral Sciences, we have organized a grant-funded digital humanities speaker and workshop series in 2015 that campus units across the disciplinary spectrum are supporting financially. All of these collaborations have resulted either directly or indirectly from the task force’s high level of engagement with the campus community in the process of its work.[pullquote]The connections we made during this process not only created momentum for digital scholarship activities on campus, but also sparked new collaborations between librarians, colleagues from other campus units, and researchers across disciplines.[/pullquote]

Before the task force started, a handful of individual librarians at CU-Boulder had expressed interest in partnering with digital scholars in their work, but no one group had stepped forward to lead the effort. The Libraries, therefore, was not able to leverage its substantial expertise – in areas such as metadata, research data management, preservation and archiving, digitization and digital content, and scholarly communication – to promote digital humanities on campus.

Our work has resulted in several significant outcomes. It has improved organizational coordination around digital humanities, increased the Libraries’ visibility as a potential partner is this endeavor, and catalyzed discussions with campus partners around a campus-wide center for digital scholarship. Further, it has highlighted the importance of our librarians not simply supporting other researchers’ work, but partnering with them on digital projects and being recognized for the intellectual contributions they make. The Libraries’ faculty, in fact, could prove an effective springboard for discussions about evaluating digital scholarly outputs for the purposes of tenure and promotion on campus. We continue to make progress as an organization though many of our suggestions have yet to be implemented. The Libraries’ Scholarly Initiatives Working Group, for instance, recently collaborated with us on a proposal and budget for a campus-wide digital scholarship center. Only time will tell how this initiative will take shape, but the findings from the task force’s multi-modal investigation have firmly established the need for a campus digital humanities initiative, and the recommendations offer a road map for getting there.

Image credit: “Needle and Thread Hi Rez” by Flickr user mikeyphillips and shared under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

![]() This written work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Images and graphics may retain other licenses.

This written work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Images and graphics may retain other licenses.

[wp_biographia user=”tlindquist”]

[wp_biographia user=”hlong”]

[wp_biographia user=”awatkins”]

![Broom: An International Magazine of the Arts, July 1922 — Cover Design by Fernand Leger [ILLUSTRATION]](https://dhandlib.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/bmtnaap192207-01.2.1-a1-700w-call-67-83-4352-6116-213x300.jpg)