My main goal in life is to build a good library of Black history – knowledge is a form of Black power and this is my part in it. – Charles L. Blockson

Introduction: Immersive Archives and Virtual Literacies

By overviewing a collaborative project between Temple University’s Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, and local Philadelphia educators, this essay explores how experimentation with immersive technology can enhance the work of librarians and teachers seeking to teach primary source literacy. As a recreation of the space and the experience of visiting the Blockson Collection through interactive game-play and multimedia 3D content, the Virtual Blockson aims to combat black erasure from the historical record and school curricula, introducing students to the roles they can play in history’s creation and preservation.

This essay will highlight the Virtual Blockson’s design for integrating the Society of American Archivists’ Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy, as well as the Common Core standards for historical understanding and critical thinking. Digital humanities projects that remediate special collections with interactive spatial simulations can offer promising opportunities to contextualize and explore the imbrication of primary source and digital literacies for marginalized communities.

The Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection

Temple University is home to a number of unique special collections containing wide-ranging primary sources, including the Paskow Science Fiction Collection and the Urban Archives of Philadelphia. Perhaps Temple’s most distinct is the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, founded in 1984 when Dr. Charles L. Blockson donated a substantial portion of his personal collection to Temple University. The collection is the direct outcome of Dr. Blockson being told by an elementary school teacher that “Negroes have no history,” a lie that he spent his life disproving by collecting everything he could relate to the lives of black people.

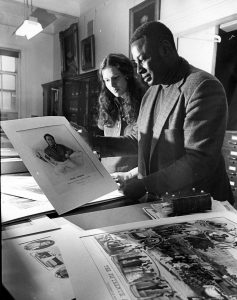

Image Caption: Charles L. Blockson holding lithograph of Frank Johnson, circa 1990s. Photo courtesy of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection

Over the decades, the Blockson has become one of the most prestigious collections of African-American artifacts in the U.S, housing over 700,000 items relating to the global black experience in multimedia formats, including books, manuscripts, sheet music, pamphlets, journals, newspapers, magazines, broadsides, posters, photographs, vinyl records, other ephemera, as well as artifacts, statues and busts, musical instruments, and dolls.

Located on Temple University’s main campus, and separate from the Temple Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center, the Blockson Collection regularly serves as a site for research and teaching. The Blockson’s Curator, Dr. Diane Turner, Associate Archivist Leslie Willis-Lowry, and Librarian Aslaku Bernahu regularly coordinate class visits and event programming meant to support awareness of the African Diaspora’s centrality to global culture and history.

Image Caption: Volunteers for MLK Day of Service at Temple University attend Open House at the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, January 21, 2019. Photograph by Bruce Turner

Across the street from the Blockson Collection, Temple University’s new Charles Library is home to the Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, a hub for researching and teaching innovative uses of technology, offering services to students and faculty, including an immersive visualization studio, a makerspace, and a specialized computer lab. Bridging these two departments, the Virtual Blockson seeks to uncover the potential for emerging technology to enhance the Blockson’s mission.

Literacies at Play

[pullquote]When mediated through emerging technologies for distant and virtual learning increasingly crucial to education today, the Blockson Collection can serve as a compelling lens through which students can analyze intersecting literacies at play in the construction of history.[/pullquote]The primary audience for the Virtual Blockson are high school students within the Philadelphia Public School System (PSD). Half of the PSD student population is black, and the other half is majority Latinx. During the 2018-2019 school year, 70.8% of Philadelphia School District students were low income. While many academic researchers are first introduced to archives as part of their college education, only 54% of PSD seniors have a first-fall college matriculation rate (for more, see the Philadelphia School District’s “School Enrollment and Demographics” data).

With all of this in mind, at least two key literacies need to be addressed by the Virtual Blockson in order to support primary source research skill development, while also adhering to existing learning standards for primary source literacy and the Pennsylvania Academic Standards for History.

The Virtual Blockson incorporates the Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy, drafted by the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and Association of College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Rare Books and Manuscripts Section (RBMS) Joint Task Force on Primary Source Literacy (JTF-PSL). According to these guidelines, primary source literacy is defined as having the competency, knowledge, or skills required to work with primary sources. Primary source literacy is inherently interdisciplinary and emphasizes flexibility depending on the learning context.

The JTF-PSL guidelines focus on students becoming familiar with 1) analytical, 2) ethical, and 3) theoretical concepts at play when utilizing primary sources, along with 4) practical considerations pertaining to access to materials, technology, and research management (JTF-PSL 3). These concepts provide guidance in assessing what each individual learning context required for primary source literacy education. They also underlie five core learning objectives and provide actionable, measurable ways to assess whether primary source researchers can 1) conceptualize; 2) find and access; 3) read, understand, and summarize; 4) interpret, analyze, and evaluate; and 5) use and incorporate the archival materials.

These learning concepts and outcomes are represented and supported in Pennsylvania’s Academic Standards for History, emphasizing analysis of artifacts, and understanding of factors influencing history. This approach hinges upon the interrogation of bias in the creation and curation of materials, and their entanglement with issues of agency, cultural heritage, and collective memory. This practice aligns perfectly with Blockson’s ideals of historical agency and knowledge for black people.

For students to learn these literacies, prerequisite skill development and onboarding must take place. In order to access the Blockson’s archival materials, PSD students have to learn how to cross the cultural and spatial lines demarcating special collections housed in universities, small repositories, and other library/museum environments that have historically ignored minority’s perspectives and restricted their access. The Blockson Collection’s very existence acts as an agent of change in rectifying the collective memory of the African Diaspora, offering an opportunity for amplifying and empowering dispossessed communities through emerging technologies.

The ways materials are contextualized within Blockson’s collection already challenge the colonial narratives of black history found in many historical collections. Blockson’s version of this narrative does not begin at slavery but situates blackness within a larger historical, social framework that also interrogates colonial depictions of that same culture and historical biases still rooted in our society. When mediated through emerging technologies for distant and virtual learning increasingly crucial to education today, the Blockson Collection can serve as a compelling lens through which students can analyze intersecting literacies at play in the construction of history.

Why Virtual Reality

[pullquote]Immersive technologies inherently introduce students to a range of literacies required for engaging with new media.[/pullquote]The Virtual Blockson project aims, in part, to serve as a vehicle for enhancing the wide array of pedagogical practices central to the Blockson Collection’s mission. Immersive technologies inherently introduce students to a range of literacies required for engaging with new media. By integrating the game-based virtual experience with learning exercises, discussion templates, and composition assignments reflecting on the learning experience, the Virtual Blockson builds upon the work of teachers and librarians already educating users in primary source literacy and digital literacy. The ability to capture screenshots and other information gleaned during the virtual archival visit can serve as reproductions available for students to cite in their scholarship. Utilizing 3D models of items from the collection set in the recreated Blockson space, gamified activities, like mapping photographs of Philadelphia, can further aid students in analyzing and critiquing the nature of archives, the role archives play in the construction of history, and the role individuals, like Dr. Blockson and the students, can have in shaping the historical record.

Multiple factors make virtual reality a suitable medium for this project’s goal of teaching primary source literacy; the most important feature is the collection’s intended audience. The Virtual Blockson does not look to replace traditional primary source literacy education efforts, wherein students visit a repository to view materials and get a better understanding of its purpose. Instead, this project aims to enhance those efforts with greater context in an engaging medium. The idea of archival intimidation (the intimidation that first-time users may experience) is one that is explored in archival literature; however, as previously discussed, there are additional layers to that intimidation that come from the intersecting identities common to PSD students. The use of virtual reality looks to immerse students in a space they may otherwise never visit while providing time and guided activities to help students deconstruct the ways they access and interact with the space and objects, as well as to understand what groups of people spaces like these tend to exclude.

The Virtual Blockson is not solely focused on primary source research; it is also focused on emphasizing the archive as an institution itself. It places students in a virtual space by introducing the user to what archives are meant to accomplish, how archives work, what to expect when visiting, and the role archives play in the production of narratives that become historical canon. The Virtual Blockson onboards students to virtual reality while guiding them through navigating the virtual space, learning the rules and etiquette of archival research, and the steps for requesting materials to inspect. Once adjusted to the environment, the Virtual Blockson simulates student learning of primary source literacy and archival research through game-based, interactive modules involving puzzle-solving and decision making. The spatialized, mobile experience furthermore reduces the distraction of students’ typical multitasking between computer screen and smartphone. By taking advantage of this relatively novel medium for interactive role-playing, by offering, for instance, opportunities to conduct the detective work of tracing the materials and construction of a musical instrument, the Virtual Blockson aims to inspire students to seek to preserve their own history and contribute to a better future for special collections and history on the African Diaspora.

Image Caption: Unity 3D virtual recreation of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, 2019. Development and screen capture by Jordan Hample

A second benefit of virtual reality is the opportunity for flexible modes of engagement. There are not only different types of immersive technologies (VR/AR/XR) but also different ways of experiencing each type of immersive technology. Virtual reality headsets like the Oculus Go offer a solitary experience for users who prefer it. However, VR headsets, especially tethered ones like the HTC VIVE, allow users to easily share their experience on a monitor so that peers can observe and engage at the same time. Smartphone-based headsets like Google Cardboard or GearVR reduce barriers to entry and increase flexibility in access, offering relatively affordable ways to introduce students to the basic affordances of 360 technologies available on their smartphones, while presenting opportunities for students to think critically about their everyday technologies capabilities and limitations.

For all users, immersive technologies, in their wide-ranging modalities, have the under-explored potential for increasing the accessibility of site-specific research. The Virtual Blockson’s success will depend in large part on the extent that we can integrate and innovate accessible user design features for navigation and interaction with archival spaces and objects.

Conclusion

[pullquote]Emerging technologies for 3D mediation, especially virtual and augmented reality, offer ways for students to recontextualize and expand their relationship to history, archival spaces, historical objects, and their existing history curricula.[/pullquote]Emerging technologies for 3D mediation, especially virtual and augmented reality, offer ways for students to recontextualize and expand their relationship to history, archival spaces, historical objects, and their existing history curricula. While pedagogical approaches to primary source literacy have evolved standards and best practices shared across fields and disciplines, the use of digital technology to enhance primary source literacy remains experimental, despite the fact that emerging 3D technologies offer novel ways to reach new audiences and guide students to think about primary source literacy as part and parcel of their literacy with emerging technologies in new media. By finding synergies between analog and digital technologies, the Virtual Blockson seeks to innovate primary source literacy pedagogy to enable playful gamification of archival research and open up new questions about the role of new media in the development of research skills.

The growing priority for education and GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) institutions to support distant learning demands new ways of thinking about how digital surrogates for primary sources can be commensurate to the spatial and interactive experience of encountering such objects in physical space for learning such essential skills as fieldwork and archival research. As virtual reality becomes increasingly mainstream, projects like the Virtual Blockson also make headway towards diversifying the available 3D assets for cultural heritage and showing a new generation of students from a wide range of backgrounds the educational potential of this emerging technology.

As an experimental innovation in digital collection development and curation more broadly, immersive technologies offer a radical new way to present archival materials to students, enhancing their familiarity with fundamental forms of digital literacy by exposing them to a multimodal, interactive environment. Such a simulation can increase student interest in visiting the physical archive and, through the embodied experience of playing the role of archival researcher, can raise student awareness about the ways that they too, like Charles Blockson, can collect their past and their present, understand their place in the world, and take agency over their own history and future.

About the Authors

Jasmine Clark is the Digital Scholarship Librarian at Temple University’s Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio. Her research focuses on accessibility and metadata for emerging technologies. She has a background in special collections, digital archives, libraries, and Black Studies.

Alex Wermer-Colan is a postdoctoral fellow at Temple University Libraries’ Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio. He has edited books of literary criticism and archival history with Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative as well as Indiana University Press. His writing also appears in The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, Twentieth Century Literature, The Yearbook of Comparative Literature, and The LA Review of Books.